METHANOTROPHS

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Methanotroph

https://ocean.si.edu/how-methane-fueled-food-web-after-gulf-oil-spill

https://smithsonianmag.com/sea-spider-species-eats-methane-with-help-of-bacteria

Sea Spider Species That ‘Eat’ Methane With the Help of Bacteria

by Sara Hashemi / June 20, 2025

“Researchers have discovered three new sea spider species that are powered by methane deep beneath the ocean. Shana Goffredi, a biologist at Occidental College and the study’s senior author, tells SFGATE that the discovery was a “happy accident.” She and her colleagues were originally researching the ecosystems around methane seeps—deep-sea ecosystems where methane gas from the Earth’s crust escapes into the ocean.

The team collected different organisms and water samples from two sites off the coast of California and one from Alaska for further analysis. That’s when they noticed the deep-sea spiders they brought back had carbon isotopes derived from methane in their tissues. Those unusual spiders, the team found, collect bacteria on their bodies, which, in turn, convert methane gas into nutrients the spiders can eat, like fats and sugars. “Just like you would eat eggs for breakfast, the sea spider grazes the surface of its body, and it munches all those bacteria for nutrition,” says Goffredi to CNN.

Even the bacteria benefit from this symbiotic arrangement—they get to live in a habitat with everything they need on the exoskeletons of the spiders. “Even if 80 percent of the population are eaten (by the spiders), it’s worth it for the 20 percent to keep surviving and reproducing,” says Nicole Dubilier, a researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology who was not involved in the work, to CNN. The findings were published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on June 16.

“Shana Goffredi, professor and chair of biology at Occidental College, doing

field research that led to the discovery of three new sea spider species.”

This discovery marks the first time scientists have observed this behavior in sea spiders. Other sea spider species, like many spiders on land, will capture and pierce their prey to suck up their internal fluids. These spiders, however, appear to lack the necessary body parts to do so. Instead, they seemingly use their teeth or “lips” to gather and eat the bacteria, either off their own exoskeletons or those of other individuals. Measuring around 0.4 inches long, the recently found species are tiny. But they hold big implications for further research: The team writes that these discoveries can help deepen our understanding of oceanic methane cycles.

“One of three methane-eating, deep-sea spider species

recently discovered off the Southern California coast”

Methane might be converted into food for these sea spiders, but it’s also a greenhouse gas that contributes to climate change. By feeding on methane, sea spiders and other deep-sea creatures like sponges and tube worms might be keeping some of the gas from reaching the atmosphere. “While the deep sea feels far away, all organisms are interconnected, and the processes in one ecosystem affect the other. The deep sea is so important. It’s involved in climate regulation, production of oxygen and supply of fisheries,” says Goffredi to SFGATE. “So, it’s really important to understand the biodiversity of these unique places.”

The study authors write that sea spiders at methane seeps are understudied, and it’s still unclear how they fit into the food webs of their environments. But because each of these species was found in a highly specific area far from the others, the team suggests that more exploration will likely unearth other methane-eating sea spider species. “People tend to think of the deep sea as a kind of homogeneous ecosystem, but that’s actually untrue. There’s a lot of biodiversity by region, and animals are very localized to specific habitats on the seafloor,” Goffredi says to CNN. “You have to be very careful if you decide to use the seafloor for mining, for example. We don’t want to cause any kind of irreparable harm to very specific habitats that aren’t found anywhere else.”

“One of three methane-eating, deep-sea spider species

recently discovered off the Southern California coast”

DEEP SEA SPIDERS

https://livescience.com/deep-sea-spiders-crawl-around-sub-antarctic-seafloor

https://sciencealert.com/deep-sea-spiders-unlike-anything-weve-seen-before

https://sfgate.com/methane-spiders-southern-california

The methane-loving critters collect gas on their exoskeleton

by Erin Rode / June 16, 2025

“Shana Goffredi didn’t plan on discovering a new species when she set out to explore the deep underwater areas off the coasts of Southern California and Alaska. Goffredi and other researchers were tasked with exploring ecosystems surrounding methane seeps, an underwater area where methane gas emerges from below the ocean floor and bubbles out into the ocean.

The U.S. Geological Survey describes methane seeps as the “occasional streams of bubbles coming up from the seafloor” in films set at the bottom of the sea. On research dives in 2021, Goffredi’s team collected a bunch of different species from these underwater habitats. Back at the lab, the team analyzed those species’ tissues “just to see if there was anything unusual about them,” said Goffredi, a professor and chair of biology at Occidental College in Los Angeles.

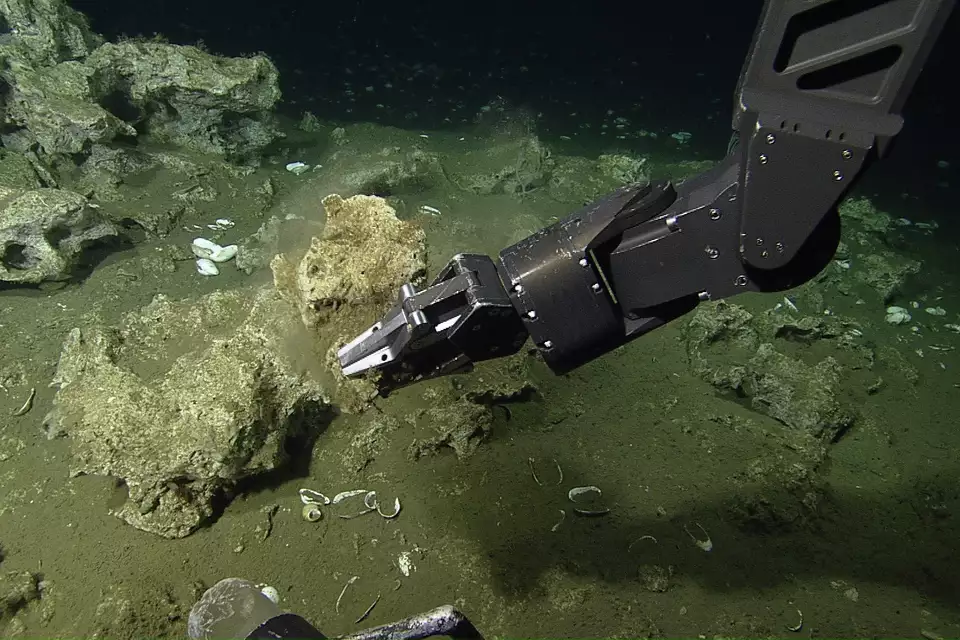

“underwater submersible collects rocks that could potentially house tiny deep-sea spiders.”

The team’s collections included deep-sea spiders, whose existence is already well-documented. But there was something different about these spiders — they appeared to be eating methane, according to an analysis of isotopes in their tissues. Goffredi and her students ultimately discovered three new species of spiders living exclusively at methane seeps and hydrothermal vents on the ocean floor, according to a paper published Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Bianca Dal Bó, a recent Occidental College graduate, is the paper’s lead author, with Goffredi listed as the corresponding author.

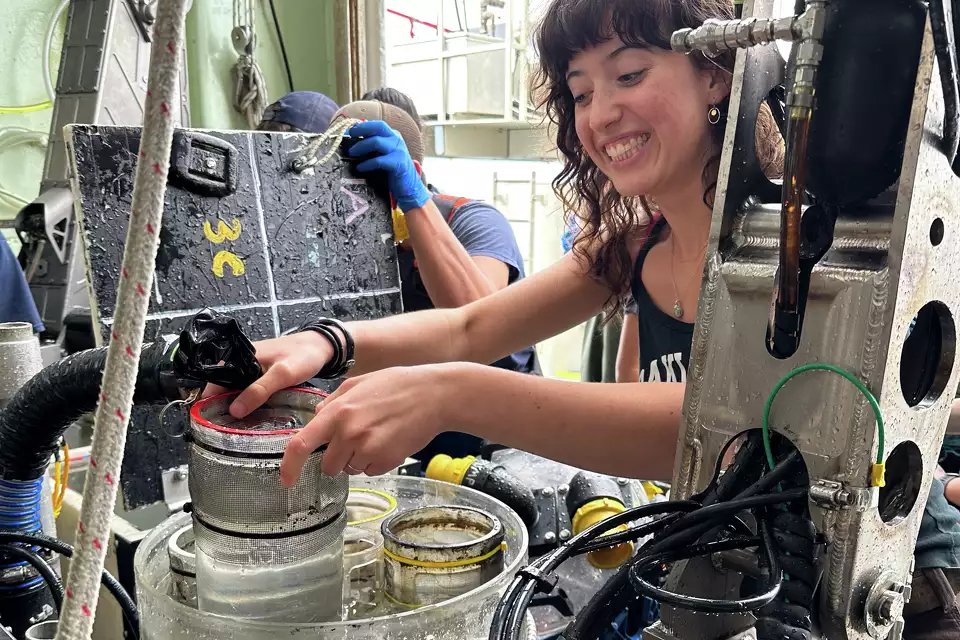

“Then-undergraduate researcher Bianca Dal Bó with samples collected by a deep-sea submersible that led to the discovery of three new sea spider species, according to a new paper that Dal Bó is a lead author of.”

The discovery shifts our understanding of how methane cycles through the ocean ecosystem, according to Goffredi, who called identifying three new spider species “a happy accident.” It also demonstrates just how little we still know about marine life deep below the ocean’s surface. “While the deep sea feels far away, all organisms are interconnected, and the processes in one ecosystem affect the other. The deep sea is so important. It’s involved in climate regulation, production of oxygen, and supply of fisheries. … So it’s really important to understand the biodiversity of these unique places,” said Goffredi.

“One of three methane-eating, deep-sea spider species

recently discovered off the Southern California coast”

Plus, sea spiders are “extremely adorable” — at least from Goffredi’s perspective. She describes the newly discovered species as “lumbering” and less nimble then its terrestrial counterparts. They’re translucent and only about a centimeter long — so tiny that when Goffredi returned to their 3,000-feet-deep ocean habitat on a spider-focused expedition in 2023, she couldn’t see them while suctioning samples deep underwater. “I came up out of the submersible all dejected because I thought we didn’t collect any, and it turned out we’d collected over 30 of them,” said Goffredi.

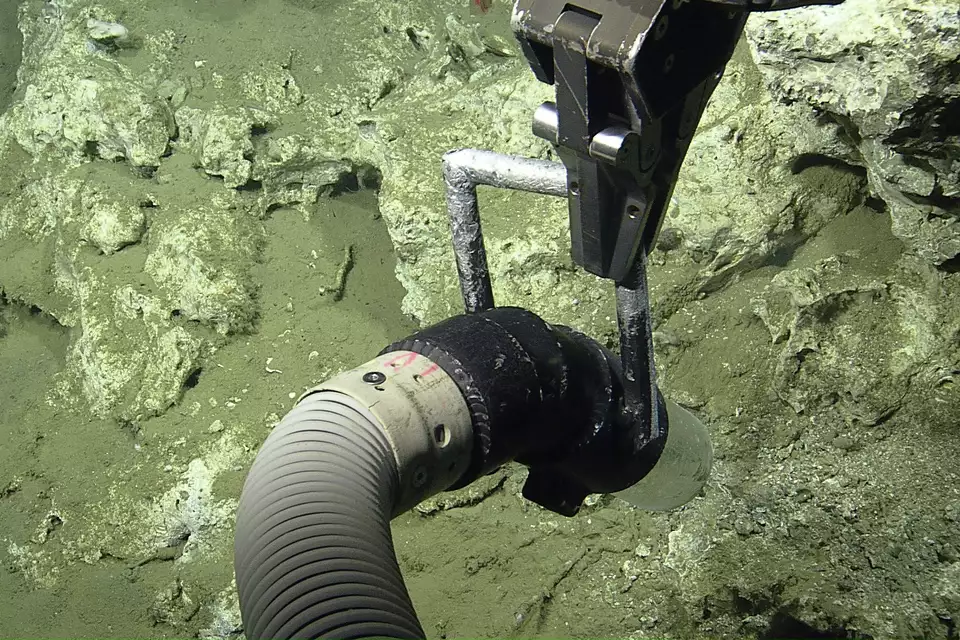

“A deep-sea research submersible slurps up water samples near a methane seep”

The team hypothesized the deep-sea, methane-seep spiders had different isotopes than expected because they fed on methane — but no animal can use methane on their own, according to Goffredi. They need help from microorganisms that can convert the methane gas into a carbon source. Terrestrial and deep-sea spiders typically pierce into the tissue of their prey, liquify the contents and then suck up that fluid. But the three spider species found by Goffredi have “a coat of methane-oxidizing bacteria on their surface,” meaning the spiders collect methane on their exoskeletons. Researchers think the spiders scrape that bacteria off with their tiny teeth. The team observed the spiders consuming methane by watching methane gas molecules move from outside of the spiders onto their exoskeletons and then into the spider tissue.

“A tiny, translucent sea spider on a carbonate rock”

The new spider species join over 1,300 sea spiders discovered so far, which range in size from 1 millimeter to 50 centimeters in leg span, according to the Monterey Bay Aquarium. Most sea spiders eat foods like anemones, worms, sponges and soft corals. Goffredi thinks there will be future discoveries of other methane-eating spiders. Each of the three species doesn’t have a very big range, and seem to be confined to their particular methane seep of choice (one species was found in the Del Mar seep, off the San Diego coast, and another was found in the Palos Verdes seep, off the Los Angeles County coastal community of the same name). Goffredi hypothesizes that 11 other sea spider species previously identified in the same genus, which are also all only found in methane seeps, likely also consume methane in this same way. The three new spiders are still unnamed — that task will fall to a graduate student at the Scripps Institute of Oceanography. But Goffredi hopes the names somehow nod to the spiders’ “methane-loving” nature. ”

“Methane-consuming serpulid worms on the seafloor off the coast of Costa Rica”

BACTERIAL (& ARCHAEAL) FARMING

https://science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.aay8562

https://theverge.com/deep-sea-mining-hydrothermal-vents

https://theverge.com/deep-sea-tube-worms-methane

Deep-sea tube worms get an assist from methane-eating bacteria

by Justine Calma / Apr 3, 2020

“Scientists exploring deep-sea seeps, where methane bubbles up out of the seafloor, have made a discovery that changes our understanding of these mysterious ecosystems. They found that two species of tube worms actually trap methane, a powerful greenhouse gas, through a never-before-seen symbiotic relationship between the worms and methane-eating bacteria. By mapping the seafloor near Costa Rica with autonomous underwater vehicles, the scientists also realized that these worms were spread out up to 300 meters farther away from the methane seeps than other organisms.

Their research, published today in the journal Science Advances, could bolster arguments to expand the boundaries used to protect ecosystems around methane seeps from deep-sea drilling and mining. “It’s really important for the health of the earth, these ecosystems. Literally every time we are in the deep sea with a submersible and collecting things we discover a new species,” says Shana Goffredi, a lead author of the study and biologist at Occidental College. “There’s so much down there that we don’t yet know about and it would be a shame to lose them.”

What first caught the researchers’ attention was that the tube worms in this particular location — a methane seep called Jaco Scar — had a “more sort of fluffy appearance,” according to Goffredi. Sometimes when animals team up with bacteria living on their bodies, they can look “fluffy” or “hairy,” Goffredi explained. Until now, bacteria that feed off the methane spewing out of these seeps hadn’t been known to live on the bodies of ocean-dwelling invertebrates like the worms. She and her colleagues brought the worms up to their ships and discovered that the two species had figured out how to farm the bacteria living on their bodies as a source of nutrition.

“It’s like having your own kind of photosynthesis, but instead of using light energy they’re using methane as the energy source,” says Victoria Orphan, a co-author and geobiologist at the California Institute of Technology. The process breaks down the methane, keeping it from eventually rising up into the atmosphere. “It’s a really smart strategy for animals in these environments to team up with microorganisms because they are really the champion chemists in these habitats,” she says. Orphan and Goffredi believe similar worms surrounding methane seeps across the world are likely doing the same thing.

The life surrounding these seeps keeps up to 90 percent of the methane leaking out of the seafloor from eventually reaching the atmosphere and heating up our planet, according to some estimates. It’s still unclear how much of a role these worms play compared to free-living bacteria known to prevent much of the greenhouse gas from escaping the ocean. But the researchers stress that damaging these ecosystems through deep-sea mining and drilling before fully understanding them could have far-reaching effects. “A lot of these systems, just like the Amazon, are poorly understood and we’re still learning about the value of these resources. Our scientists are kind of in this race to at least establish a baseline to better inform conservation efforts,” says Orphan. “Even though [this ecosystem is] remote, that doesn’t necessarily mean that there isn’t a connection to us.”

PREVIOUSLY

ABRUPT THAWING

https://spectrevision.net/2019/10/09/abrupt-thawing/

DEEP HOT BIOSPHERE

https://spectrevision.net/2020/01/27/deep-hot-biosphere/

LIFE WITHOUT SUNLIGHT

https://spectrevision.net/2021/06/01/subsurface-biomes/

MANY ORIGINS of LIFE

https://spectrevision.net/2024/03/14/many-origins-of-life/

ABIOTIC METHANE

https://spectrevision.net/2024/04/18/fossil-fuels-in-space/

DARK OXYGEN

https://spectrevision.net/2024/07/24/dark-oxygen/