see also: AL SMITH HOUSING LAW, 1920

https://economics.ucr.edu/papers/papers01/01-01.pdf

https://economics.ucr.edu/papers/papers06/06-06old.pdf

NY STATE LAND VALUE TAX PILOT PROPOSAL SEEKS CO-SPONSORS

https://progressandpoverty.substack.com/p/the-lvt-movement-across-US

https://progressandpoverty.substack.com/p/land-value-tax-hits-the-news

https://news10.com/land-value-tax-pilot-program-proposed-to-make-housing-affordable

Land value tax pilot proposal to make New York housing affordable

by Johan Sheridan / Apr 15, 2025

“On the eve of Tax Day, Democratic state legislators introduced a bill that would shift property taxes to a land value tax. Sponsors say transforming the current system would blunt the effects of the housing crisis statewide. Land value taxes levy the value of unimproved land itself, rather than buildings or improvements on it. Taxing the value of the land itself is supposed to discourage property owners from speculation—holding onto vacant or underutilized land while waiting for prices to rise, a major factor driving up unaffordability—while encouraging them to develop the property for housing. State Senator Rachel May proposed S1131A/A3339A alongside Assemblymembers Tony Simone and Alex Bores. They said that the current system lets landowners pay less than they should for the real value of a property. Plus, it puts an arbitrary or potentially damaging limit on a finite, in-demand public resource.

The proposal would realign tax incentives, reduce wasted urban space, and prioritize long-term, community-oriented goals in New York’s housing market. It would establish a pilot program in as many as five municipalities statewide, wherein the Department of Taxation and Finance would classify real estate in two groups: land only and buildings on land. The program would impose a higher tax rate on land and a lower rate on buildings, spurring construction and lowering housing costs. “Implementing a land value tax in New York could be a powerful tool to unlock underutilized land, incentivize development, and create a more equitable and efficient housing market,” Simone said. To apply, local elected bodies would have to pass a law, and local school districts would have to pass a resolution. Municipalities with over 50,000 residents could carve out a particular neighborhood or area to participate in the pilot. The tax department would then notify the municipality’s chief executive and the leaders of the Assembly and State Senate once selected.

This approach and similar reforms spurred economic growth and improved urban spaces in other states, according to experts at the Center for Land Economics and the Community Service Society of New York. The bill would abandon the current “ad valorem”—Latin for “according to value”—system. Land value tax would pressure those who sit on empty land instead of rewarding them with low tax bills to drive up local housing. The change could increase affordable housing, reduce homelessness, and assess fairer tax bills for people struggling with rising costs of living. “In November, New York’s voters spoke loud and clear that cost of living remains a central issue,” Bores said. Bores, Simone, and May circulated a link to a petition that New Yorkers can sign onto in support of their legislation.”

LAND VALUE TAX STATE LEGISLATION

https://landeconomics.org/lvt-legislation

https://buffalorising.com/council-resolution-explore-land-value-taxation

https://centralcurrent.org/how-a-state-bill-could-reshape-property-taxes

How a state bill proposed could reshape property taxes and spur development

by Patrick McCarthy / January 27, 2026

“Mayor Sharon Owens believes a bill proposed in the state legislature that would alter how property is taxed could also spur development in Syracuse at a critical time. The Land Value Tax bill, sponsored by state Sen. Rachel May, would create a pilot program to shift the way land is assessed and taxed. The legislation would allow cities to tax the value of land itself rather than the structures built on the land, replacing a traditional property tax. Proponents of the policy say it would incentivize development, discourage speculative land hoarding, generate tax savings for residential property owners and ensure that any publicly generated increase in land values benefits the broader community. They argue a land value tax could also reduce the tax burden for lower-income residential property owners while incentivizing developers to develop their land or sell it.

According to a 2025 analysis of the land value tax model in Syracuse, advocates for the policy calculate that a shift in taxation made possible by May’s bill would bring in a reduction in property taxes to almost every residential neighborhood in the city. In an interview with Central Current, Owens explained that she is still learning more about the legislation and its local ramifications, but said she supports the concept of shifting the way Syracuse levies taxes. “It is, to me, de-incentivizing people to tear down,” Owens said. The Land Value Tax bill was proposed in 2025 and was most recently sent to a committee in the state Senate.

Land value tax supporters consider downtown parking lots and parking buildings a prime example of underused land that could be developed. During a recent interview, Owens gestured toward a parking lot across the street from City Hall while describing impediments to downtown development. “Like that’s a sea of parking over there, a sea of parking. Minimally, build a parking garage that you can build more parking in,” Owens said. “But really, in high-demand city spaces, surface parking lots are not the best, and we don’t own them. And so I am learning more about it.” Zach Zeliff, May’s chief of staff, and Councilor Corey Williams since last year have explored how a land value tax could affect Syracuse. May’s proposal overlapped with Williams’ goals: to find a way to combat vacant properties and underused land. Williams, who chairs the Common Council’s Finance and Taxation Committee, initially considered a vacant lot fee or a fee on speculation, which Zeliff told Willams would be hard to implement. “And land value tax incorporates both of those concepts into one tool,” Williams said.

Williams said the idea has found support locally from both housing advocates and developers, stakeholders typically at odds on housing and development policies. “I think any tool that we have that can promote development of underutilized parcels, that can discourage speculation, that can incentivize investment in properties and potentially reduce the tax burden on residents,” Williams said, “it’s something we should be exploring.” Under May’s proposed bill, cities like Syracuse could opt into using a split-rate taxation system. Property taxes would be replaced with a new rate made up of two components: A tax on the value of the land owned by the property owner and a rate for the value of the buildings on the land. The tax on the land would be weighted more heavily than the tax on the structures.

While the approach is novel, it isn’t new. Cities in Pennsylvania are allowed to adopt a land value tax model. Pittsburgh and Harrisburg each have shifted toward a land value tax. New York state in 1993 briefly allowed the city of Amsterdam to enact a short-lived land value tax through home rule legislation. Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan in 2023 proposed a land value tax, but state legislation to allow Michigan cities to adopt a land value tax stalled in the state legislature. Under the proposal, Detroit would have doubled the property tax rate on land while cutting the tax rate for buildings by 70%, according to Outlier Detroit.

The concept of levying a land value tax dates back centuries. The philosophers and economists Adam Smith and John Stuart Mill supported taxing land as a means to encourage development. The Gilded Age economist and social reformer Henry George advocated for the model in his 1879 text “Progress and Poverty,” which examined and proposed solutions to growing wealth inequality amid technologically advancing industrialized societies. Though the idea is sometimes associated with progressive politics, free market economist Milton Friedman in 1978 called the land value tax model the “least bad tax.”

Greg Miller, the co-founder and director of the Center for Land Economics, in 2025 created a report simulating how that policy would affect Syracuse, if Albany were to approve May’s legislation. Miller believes the scarce adoption of the land value tax doesn’t reflect a lack of popularity, but rather, a lack of pressure. As American cities grew more dense and populous in the 1930’s and 1940’s, outward development of suburbs and highways eased the pressure on urban areas.

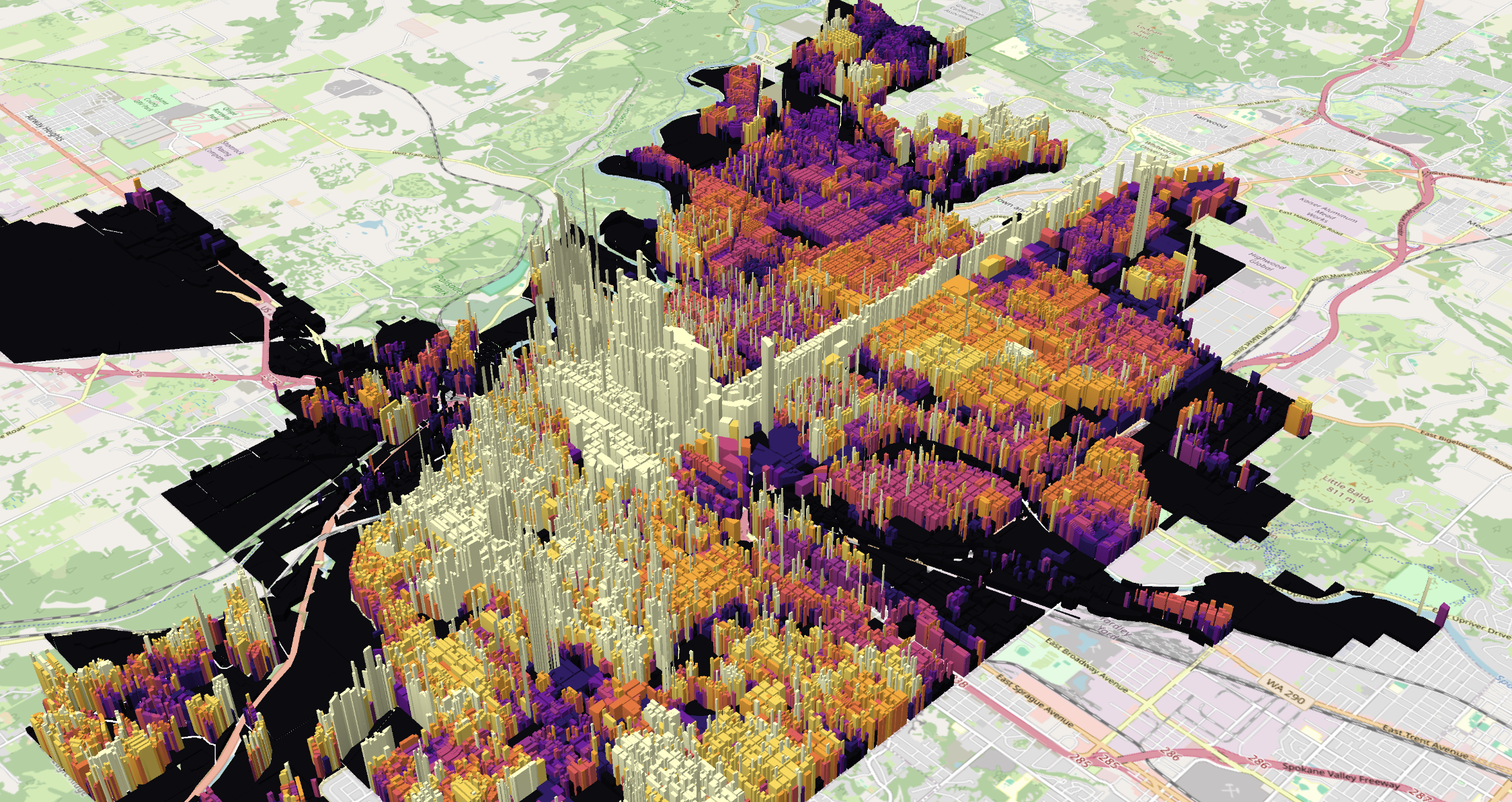

“CivicMapper is an interactive parcel map with cloud-hosted cities that

reveals where value is concentrated — and where land is underused.”

But now, cities everywhere are becoming denser and feeling that pressure, Miller said, and it has resulted in renewed interest in the land value tax model. “I don’t think of the housing crisis necessarily as a housing crisis, as much as I think of it as a land value crisis,” Miller said. “We’re starting to see land values really skyrocket in a lot of areas. When people are complaining about their property taxes increasing, they didn’t build anything new on their house, but their property tax bill increased. The reason that’s true is because the land value has increased.”

Miller’s analysis kept Syracuse’s property tax levy neutral — but shifted how the tax on the land is calculated. In Miller’s report, he created a tax rate in which about 80% of the value comes from a tax on the land and 20% comes from a tax on structures. He found that such a shift in Syracuse would reduce the tax burden on residential property owners but increase the tax burden on the owners of parking lots and vacant land in areas like downtown.

Property taxes on the median home in residential neighborhoods like the Near West Side, Near East Side, Southside and Southwest could fall by 20% or more, Miller wrote in the report. “The way I think about it is the property tax is two taxes in one: it’s a building tax and a land tax. And we need more buildings, yet we tax buildings. And we need less land speculation, yet we don’t tax land enough,” Miller said. “And so by implementing a revenue neutral policy … we’re shifting taxes from buildings, which we want more of, to land and the value of land.”

In the past year, six states, including New York, have introduced legislation to enable cities to implement a policy to enable cities to enact land value tax. City Auditor Alex Marion believes a land value tax shift would be one of the most effective tools for taxation that New York state has introduced in years. If Albany enacts May’s legislation and allows cities to shift to a land value tax model, Marion believes the policy won’t just stimulate development, but revenue, too. “We have to acknowledge that we have a tax exempt property crisis in Syracuse,” Marion said. “…When one of your top three largest sources of revenue is property taxes, and 53% of your property is not taxable, you have a math problem.”

As Syracuse officials consider how to make the most of regional investment, the land value tax shift has supporters across city government as well as the state capital. “We’re trying to make sure that folks really develop land, and that land is used to create a more vibrant city,” Miller said. “And so I think that this is the exactly right tool to use to align market incentives towards development, particularly on valuable land in the downtown area of Syracuse.”

PREVIOUSLY

STATELESS PROPERTY OWNERS

https://spectrevision.net/2015/01/14/stateless/

TAXING VACANCIES

https://spectrevision.net/2018/03/29/taxing-vacancies/

LAND VALUE TAX

https://spectrevision.net/2019/09/19/land-value-tax/

TAXING BLIGHT

https://spectrevision.net/2023/06/14/taxing-blight/

ONLY TAX MILLIONAIRES

https://spectrevision.net/2024/05/29/city-of-millionaires/

a SINGLE TAX

https://spectrevision.net/2025/01/15/a-single-tax/