HOW to CALCULATE YOUR RESOURCE WEALTH

http://www.europeanenergyreview.eu/index.php?id=1101

http://books.google.com/books?id=yk5NI69ZO9sC

http://www.usbig.net/links.html

‘CITIZEN’S DIVIDEND’

http://www.thomaspaine.org/Archives/agjst.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Citizen’s_dividend

Citizen’s dividend or citizen’s income is a proposed state policy based upon the principle that the natural world is the common property of all persons (see Georgism). It is proposed that all citizens receive regular payments (dividends) from revenue raised by the state through leasing or selling natural resources for private use. In the United States, the idea can be traced back to Thomas Paine’s essay, Agrarian Justice[1], which is also considered one of the earliest proposals for a social security system in the United States. Thomas Paine best summarized his view by stating thateurasia “Men did not make the earth. It is the value of the improvements only, and not the earth itself, that is individual property. Every proprietor owes to the community a ground rent for the land which he holds.”

This concept is a form of basic income, where the Citizen’s Dividend depends upon the value of natural resources or what could be titled as “common goods” like seignorage, the electro-magnetic spectrum, the industrial use of air (CO2 production), etc. The State of Alaska dispenses a form of citizen’s dividend in its Permanent Fund Dividend, which holds investments initially seeded by the state’s revenue from mineral resources, particularly petroleum. In 2005, every eligible Alaskan resident (including their children) received a check for $845.76. Over the 24-year history of the fund, it has paid out a total of $24,775.45 to every resident.

BASIC INCOME

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Basic_Income

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Georgism

http://www.basicincome.org/bien/aboutbasicincome.html

http://www.basicincome.org/bien/papers.html

http://www.multinationalmonitor.org/mm2009/052009/interview-widerquist.html

MM: What are the origins of the concept?

Widerquist: Some people trace the idea back as far as ancient Greece. The idea started appearing gradually in different times and places in the modern era. Thomas Paine mentioned something like it in his pamphlet “Agrarian Justice” in the 1790s. Bertrand Russell articulated the idea in 1915. Economists started talking about the idea in the 1940s. The idea gathered a great deal of attention in the United States in the 1960s and 1970s, when people began to think of it in very diverse ways: as the scientific solution to poverty, as a streamlined yet more effective alternative to the welfare state or as a way to empower the least advantaged people. At one point, it seemed like the inevitable next step in social policy. People as diverse as Martin Luther King and Richard Nixon endorsed it. Groups as diverse as chambers of commerce and grassroots welfare rights campaigners endorsed it. But the diversity of its appeal was matched by the diversity of its opposition. A watered-down version of it called “the Family Assistance Plan” passed narrowly in the House of Representatives in 1972, but was defeated in the Senate by a coalition of people who thought it went too far and people who didn’t think it went far enough. Interest in the idea dropped off in the United States in the late 1970s, but then interest began to grow in Europe. The academic debate has continued to grow ever since and it has translated into popular movements in places as diverse as Ireland, Namibia, Finland, Brazil, South Africa, Belgium, Germany and Italy.

MM: Are there examples of policies being enacted? How have they turned out?

Widerquist: Yes, there are a few small things around the world and one big example in Alaska. Brazil recently voted to combine several of its anti-poverty programs into a program called the Bolsa Familia, which is supposed to be the first step. A private NGO is currently conducting a pilot project in Namibia with great success. The Alaska Permanent Fund (APF) has been in place for 25 years. The “basic” in basic income guarantee is meant to indicate that it is enough to cover your basic needs. The APF isn’t that large, but it is one of the most popular government programs in the United States today. They had a referendum proposing to get rid of it a few years ago, and people voted something like 85 percent in favor of keeping it. Few government programs have that kind of support. The APF is another outgrowth of the NIT movement in the United States in the 1970s. Jay Hammond was governor when the Trans-Alaska Oil Pipeline was proposed. He had learned about BIG during the NIT debate, and he saw the opportunity to connect the two. Usually when businesses want to take publicly owned natural resources and make them into private property, they just pay off the right politicians and they get the resources free or at a nominal fee. But Hammond decided that this oil belonged to all the people of Alaska, and if the corporations wanted to buy it, they had to pay into a fund that would pay a yearly dividend to every citizen in Alaska. The APF dividend varies year-to-year depending on the fund’s returns. It’s usually somewhere between $1,000 and $2,000. Last year the dividend was a record high of $3,200. Of course, $3,200 isn’t enough to meet anybody’s basic needs, but it can make a huge difference for people at the margins. Suppose you’re a single parent with four children living on an Indian reservation somewhere in Alaska. Last year’s APF Dividend was worth $16,000 to you and your family. You can’t live on that all year, but imagine the difference it makes. You might worry that people who get a check from resource revenues might be more accepting of resource exploitation. But other factors, I believe, more than counteract any such effect. Remember that today companies are taking control of natural resources all over the planet and paying no compensation at all to the rest of humanity. If you want people to do less of something, taxation is a very good way to start. If you tax resource extraction, you not only discourage people from doing too much of it, you also establish the precedent that natural resources belong to everyone — not just to the first corporation to get permission from the government. That precedent would be enormously valuable to the environmental movement.

STEP ONE : LOCATE RESOURCES

http://www.npr.org/blogs/money/2010/06/14/127834173/will-afghanistan-fall-victim-to-the-resource-curse

http://www.npr.org/blogs/money/2010/06/17/127915306/one-way-to-break-the-natural-resource-curse-give-the-money-away

Afghanistan’s big deposits of lithium, copper and gold have some economists worried. As we noted earlier this week, the discovery of natural resources often leads to conflict and corruption, which in turn hurt economic growth. But a handful of economists are pushing an idea they say could break the natural resource curse. Take all money that comes in from foreign companies — for lithium in Afghanistan, oil in Nigeria, natural gas in Bolivia — and give it to the citizens. Literally have a government official sit down with piles of cash, maybe with some international oversight, and divvy it up. That system would create a strong incentive for the people to keep on eye on what the government’s doing, says Todd Moss of the Center for Global Development. “If you received $500 last year, and this year it’s only $400, you’re going to ask some pretty hard questions,” he says.

But there are a few key barriers to putting the plan into action. The first is logistics. Lots of resource-rich countries don’t have national databases, clear census records or strong banking systems. That makes it tough to hand out billions of dollars to millions of people, year after year. The second is the fact that money is power. A government that’s getting lots of money by selling natural resources may be reluctant to share the wealth. Arvind Subramanian, an economist with the Peterson Institute, recently traveled to Nigeria to pitch the idea of giving oil revenues directly to the people. The government wasn’t interested. “If the current guy in power does not want to give up power, my idea has no hope of succeeding,” Subramanian said.

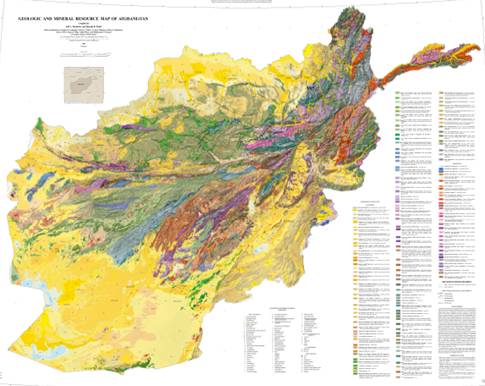

‘SAUDI ARABIA of LITHIUM’

http://earth2tech.com/2010/06/14/who-wants-afghanistans-lithium-chinas-electric-vehicle-players/

http://afghanistan.cr.usgs.gov/flash_tile.php?cat=NRL%20Aerial%20Photography%20preliminary%20Data

http://afghanistan.cr.usgs.gov/airborne.php

http://www.usgs.gov/newsroom/article.asp?ID=1819

http://www.bgs.ac.uk/downloads/browse.cfm?sec=7&cat=83

http://www.bgs.ac.uk/afghanminerals/raremetal.htm

http://www.bgs.ac.uk/AfghanMinerals/links.htm

http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/afghanistans-resources-could-make-it-the-richest-mining-region-on-earth-2000507.html

Afghanistan’s resources could make it the richest mining region on earth

by Kim Sengupta / 15 June 2010

Afghanistan, often dismissed in the West as an impoverished and failed state, is sitting on $1 trillion of untapped minerals, according to new calculations from surveys conducted jointly by the Pentagon and the US Geological Survey. The sheer size of the deposits – including copper, gold, iron and cobalt as well as vast amounts of lithium, a key component in batteries of Western lifestyle staples such as laptops and BlackBerrys – holds out the possibility that Afghanistan, ravaged by decades of conflict, might become one of the most important and lucrative centres of mining in the world. President Hamid Karzai’s spokesman, Waheed Omar, said last night: “I think it’s very, very big news for the people of Afghanistan and we hope it will bring the Afghan people together for a cause that will benefit everyone.” In Washington, Pentagon spokesman Colonel David Lapan, told reporters that the economic value of the deposits may be even higher. “There’s … an indication that even the £1 trn figure underestimates what the true potential might be,” he said. According to a Pentagon memo, seen by The New York Times, Afghanistan could become the “Saudi Arabia of lithium”, with one location in Ghazni province showing the potential to compete with Bolivia, which, until now, held half the known world reserves.

Developing a mining industry would, of course, be a long-haul process. It would, though, be a massive boost to a country with a gross domestic product of only about $12bn and where the fledgling legitimate commercial sector has been fatally undermined by billions of dollars generated by the world’s biggest opium crop. “There is stunning potential here,” General David Petraeus, the US commander in overall charge of the Afghan war, told the US newspaper. “There are lots of ifs, of course, but I think potentially it is hugely significant.” Stan Coats, former Principal Geologist at the British Geographical Survey, who carried out exploration work in Afghanistan for four years, also injected a note of caution. “Considerably more work needs to be carried out before it can be properly called an economic deposit that can be extracted at a profit,” he told The Independent. “Much more ground exploration, including drilling, needs to be carried out to prove that these are viable deposits which can be worked.” But, he added, despite the worsening security situation, some regions were safe enough “so there is a lot of scope for further work”.

The discovery of the minerals is likely to trigger a commercial form of the “Great Game” for access to energy resources. The Chinese have already won the right to develop the Aynak copper mine in Logar province in the north, and American and European companies have complained about allegedly underhand methods used by Beijing to get contracts. The existence of the minerals will also raise questions about the real purpose of foreign involvement in the Afghan conflict. Just as many people in Iraq held that the US and British-led invasion of their country was in order to control the oil wealth, Afghans can often be heard griping that the West is after its “hidden” natural treasures. The fact US military officials were on the exploration teams, and the Pentagon was writing mineral memos might feed that cynicism and also motivate the Taliban into fighting more ferociously to keep control of potentially lucrative areas.

Western diplomats were also warning last night that the flow of money from the minerals is likely to fuel endemic corruption in a country where public figures, including Ahmed Wali Karzai, the President’s brother, have been accused of making fortunes from the narcotics trade. The Ministry of Mines and Industry, which will control the production of lithium and other natural resources, has been repeatedly associated with malpractice. Last year US officials accused the minister in charge at the time when the Aynak copper mine rights were given to the Chinese, Mohammed Ibrahim Adel, of taking a $30m bribe. He denied the charge but was sacked by President Karzai. But last night Jawad Omar, a senior official at the ministry, insisted: “The natural resources of Afghanistan will play a magnificent role in Afghanistan’s economic growth. The past five decades have shown that every time new research takes place, it shows our natural reserves are far more than what was previously found. This is a cause for rejoicing, nothing to worry about.”

According to The New York Times, the US Geological Survey flew sorties to map Afghanistan’s mineral resources in 2007, using an old British bomber equipped with instruments that offered a 3-D profile of deposits below the surface. It was when a Pentagon task force – charged with formulating business development programmes and helping the Afghan government develop relationships with international firms – came upon the geological data in 2009, that the process of calculating the economic values began. “This really is part and parcel of General [Stanley] McChrystal’s counter-insurgency strategy,” Colonel Lapan said yesterday. “This is that whole economic arm that we talk about but gets very little attention.”

‘DISCOVERY’

http://www.state.gov/secretary/rm/2010/05/141825.htm

http://www.defense.gov/transcripts/transcript.aspx?transcriptid=4643

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/15/world/asia/15afghan.html?ref=global-home

http://blog.foreignpolicy.com/posts/2010/06/14/more_on_afghanistans_mineral_riches

http://ricks.foreignpolicy.com/posts/2010/06/14/minerals_in_afghanistan_mais_oui

by John Stuart Blackton

The ” discovery” of Afghanistan’s minerals will sound pretty silly to old timers. When I was living in Kabul in the early 1970’s the USG, the Russians, the World Bank, the UN and others were all highly focused on the wide range of Afghan mineral deposts. The Russian geological service was all over the North in the 60’s and 70’s. Cheap ways of moving the ore to ocean ports has always been the limiting factor. The Russians were looking at a northern rail corridor. Take a look at this little bibliography of Afghan mineral assessments. This one is mostly Russian, but pre-dates the DoD/USG “discovery” period by 30 years. In my day we did a joint USG/Iranian study of a potential rail line from Afghanistan to several of the Iranian rail hubs. This was predicated on mineral exploitation in a way that would thwart the Russian’s northern rail corridor plans. In the early 70’s the USG had an old FDR New-Deal planner/economist/brains-truster – Bob Nathan – working with the Afghan Ministry of Plan to work out a fifty year mineral exploitation program. When the Russians took over they picked up Bob’s plans and extended them. So this is anything but a “new discovery”. Low cost, long haul transport infrastructure remains the constraint.

{John Stuart Blackton, who has shaken more Helmand River sand out of his shorts than most Americans in Afghanistan have walked on, provides some background. By the way, before running USAID in Afghanistan, John attended Stephens College of Delhi-as did Pakistan’s Gen. Zia.}

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6X-nXvBh7UQ]

STEP TWO : DETERMINE TRUE COSTS

http://reclaimdemocracy.org/corporate_welfare/

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/General_Mining_Act_of_1872

http://www.seattlepi.com/specials/mining/26875_mine11.shtml

The General Mining Act of 1872

by Robert McClure & Andrew Schneider / June 11, 2001

Gold, silver, platinum and other precious metals for free. Land for $5 an acre or less. That’s the deal mining companies get from the U.S. government when miners turn their explosives and earthmovers toward public land in the West. It’s pretty much the same deal miners have had for 129 years, ever since Congress approved the General Mining Law in 1872. Modern mining methods have left the West pockmarked by huge craters, some so large that they are visible from space. Whole mountainsides are ground to dust and doused with cyanide, teasing out enough gold for a single wedding ring from several tons of rock and soil. And tens of thousands of abandoned mines scar the landscape, many emitting an orange-red, acid-laced runoff called “yellow boy.” These mines have poisoned more than 16,000 miles of Western streams. When a mine goes bankrupt, taxpayers sometimes get stuck with the costs of cleaning up the mess — more than $275 million for three mines alone in Colorado, South Dakota and Montana that closed in the 1990s. Under terms of the antiquated law, miners cart away everything from gold to kitty litter from public lands — minerals worth about $11 billion in the last eight years alone. Not only does the U.S. Treasury get nothing, Congress has granted miners a tax break worth an estimated $823 million in the coming decade. Over the years, public lands the size of Connecticut have been made private under terms of the 1872 law, all for $2.50 to $5 an acre, though not all of it has been used for mining. Some claims became ski resorts, housing subdivisions, hotels and even a brothel, in Nye County, Nev.

Congress has acted over the years to rein in some abuses allowed under the act, but problems persist, and the debate over the future of Western lands continues. New mining regulations designed to protect taxpayers and the environment went into effect just hours before George W. Bush became president — and he soon moved to get rid of them. A watered-down version of the rules or a full suspension is expected next month. The controversy over the new regulations for administering the old law is just one more battle in a land-use war that has raged for generations. It’s a complex subject, rich in history. But the issues boil down to three broad areas of disagreement: To what degree mining harms the environment, whether the jobs it produces are worth the damage, and whether the public interest is being subverted by the miners and their friends in Washington, D.C.

Opening the West

Complaints about a taxpayer rip-off started just about as soon as miners arrived in the vast American West. Trying to establish order amid the chaos of the California gold rush in 1848, an Army colonel named Mason sent a dispatch to headquarters warning: “(T)he government is entitled to rents for this land, and immediate steps should be devised to collect them, for the longer it is delayed the more difficult it will become.” Nearly two decades later, Congress adopted the Lode Law of 1866 — a troubled bill that won passage because it was attached to unrelated legislation. The 1866 law, updated in 1870 and in 1872, probably wasn’t what Colonel Mason had in mind. It simply legitimized what miners were already doing: Find a bit of federal land that appears to contain gold, silver or other “hard-rock” minerals, pound stakes at its corners to warn off others, dig, and — if you guessed right — cash in.

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hY-tIEqzcmU]

Like the better-known Homestead Act, which offered free land to anyone willing to farm it, the mining law was intended as an incentive to those willing to push West and settle the frontier. That frontier was closed long ago, but the mining law remains on the books and very much in use — even where mining would harm an increasingly settled region. The new mining regulations targeted for repeal by the Bush administration give the government the right to reject a proposed mine if it would cause “substantial irreparable harm.” Currently, federal officials must administer a law they say promotes mining as the best use of millions of acres of federal land, even in sensitive places such as Top Of The World, Ariz., a wide spot in the road 70 miles from Phoenix. There, a Canadian company called Cambior wants to dig copper where wild boars roam and the hedgehog cactus blooms brilliant red in the spring. The sulfuric acid, trucks, noise and dust from a 24-hour-a-day mine would be plopped down just upstream from a lush, tree-shaded canyon — a rarity there.

Cambior, which also ran a mine in Guyana where 300 million gallons of a cyanide-bearing solution spilled, wants to dig three pits covering nearly a square mile, reaching a depth of 600 feet. The hundreds of millions of tons of earth removed would be piled into heaps covering an additional square mile-plus. The ore, the material that bears copper, would be doused with 400 tons of sulfuric acid per day. To do this, the company would reroute more than two miles of streams, some through channels constructed of a concretelike material. The Canadian firm and its subsidiary, Carlota Copper Co., will pay no more than $1,700 for the public portion of the land it would mine. The company expects to mine some 478,000 tons of copper worth about $728 million at current prices. Even a federal lawyer trying to defend the government’s approval of the mine had to admit, “The circumstances here include a proposed project that is so invasive to the forest that it would never be considered, much less approved, were it not for the mining law of 1872.” And a federal judge handling a suit by environmentalists who tried to stop the project ruled that the mining law trumps their concerns. “Because mining has been accorded a special place in the national laws related to public land, the development of mineral resources in the national forests may not be prohibited or unreasonably circumscribed,” U.S. District Judge Paul Rosenblatt wrote. “The Forest Service consequently has no authority to categorically reject an otherwise reasonable mining plan of operations.”

Bob Walish, manager of the Cambior project, said it is misleading to consider only the $5 per acre the company will pay the government. He said the company spent about $61 million prospecting, obtaining permits and fighting lawsuits. Echoing the industry’s supporters in Congress, Walish said the government should follow through with the intent of the mining law — to privatize land in the West. More than half of some states are still owned by the government, he noted. “The debate in our mind isn’t that we’re stealing this from the public,” he said. “It’s ‘Why is there (still) all this public land?'” Stephen D’Esposito, president of the Mineral Policy Center, an environmental group dedicated to mine-law reform, points to Top Of The World and places like it when asked what’s wrong with the 1872 law. “It’s time for a new deal that keeps our water clean, protects our public lands from destructive mineral development, eliminates corporate subsidies and gives the taxpayer a fair return,” D’Esposito said. “What’s needed are three common-sense reforms: the right of the public to say ‘no’ when mining isn’t the best use of our public lands; a requirement that mining companies pay to clean up their messes as a cost of doing business; and a provision that mining companies pay taxpayers a fair price for mining on public lands.”

An economic savior

Though less of an economic force than in the past, mining remains an economic savior of some rural areas in the West, where more than 100 hard-rock mines are operating. And those who run the international corporations that have replaced the pick-and-shovel prospectors of the 1800s say the public still benefits from their hard work and willingness to risk a fortune to develop mines that might not return one. They point out that mining still pays better than most jobs in the rural West, and they note that mining firms and their employees pay taxes, too. And society gets something it can’t live without, they argue: metals. U.S. manufacturers get about half their metals from right here at home. “Mining makes our civilization…. Everything you do today depends on mining,” Rep. Jim Gibbons, R-Nev., a former mining geologist, said at a recent congressional hearing. Before another hearing, Gibbons said that efforts to crack down on mining companies “may relegate us to a Third World status.”

The miners say they are regulated enough. The government already has put about 165 million acres off-limits, and on an additional 182 million acres, the U.S. Forest Service or the Bureau of Land Management can reject mining permits. That leaves about 350 million acres of the West open to mining. And miners note that the law doesn’t excuse companies from having to abide by more-recent federal laws such as the Clean Water Act and the National Environmental Policy Act. “We can’t mine in parks. We can’t mine in sensitive areas,” said Jack Gerard, president of the National Mining Association. “The government every day makes public lands/public policy decisions.”

Yet exercising this power can be expensive. In 1995, President Clinton proposed a ban on mining in an area near Yellowstone National Park. A Canadian firm, Crown Butte Mines Inc., already had applied to privatize some land in the area and planned to use land already patented — that is, converted to private property by others who paid a small fee. The government had to pay $65 million to stop the mine. The money went to Battle Mountain Gold, which had bought Crown Butte. Battle Mountain Gold wants to open Washington state’s first major open-pit gold mine, the Crown Jewel project in Okanogan County. The 1872 Mining Law has been under fire for decades, but the industry has been able to head off countless attempts at reform. One of its bedrock arguments is that overhauling the law would risk national security. “Destroying the mining law will risk the lives of our sons and daughters, for many will surely die in battle on some foreign shore because of it,” said Richard Lawson, a retired four-star Air Force general who until recently headed the National Mining Association. “Without the protection of the mining law, America cannot get the minerals it must have to remain free and secure, and we will go to war to get those precious metals.” But some Western communities pay a high price for this freedom.

Superfund sites abound

Signs near Spokane carry an ominous warning: “This health advisory is posted to alert you to the presence of elevated levels of lead and arsenic in soils along the shorelines and beaches of the upper Spokane River…. Swallowing or breathing loose shoreline soils may be an increased health risk to people, especially infants, small children and pregnant women.” The signs, posted by the Spokane Regional Health District, warn that children shouldn’t play in muddy soils along the river and should be closely supervised to ensure that they don’t put dirt in their mouths. Toxic goop is spilling into Washington fully 50 miles downstream from the Silver Valley, where North Idaho miners dug silver, lead and other metals from the earth for more than a century. The Spokane flows from Coeur d’Alene Lake, which the Environmental Protection Agency says holds some 70 million tons of mining waste — enough to cover a football field 4.7 miles high. And rivers all across the West are tainted by old mines, including the Columbia and the Okanogan in Washington.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s roster of the nation’s worst industrial contamination hot spots, the so-called Superfund list, includes more than 25 mines, a handful still active. Cleaning them up will cost billions of dollars. Whole towns in Montana and Idaho have been swallowed by Superfund sites, their stream banks and hillsides denuded of plants. In Idaho’s Silver Valley, the source of the mine waste in the Spokane River, tests show that one in six children under age 6 have enough lead in their bodies to affect learning and other functions. While much of the damage done by mining in the West happened decades ago, environmental problems continue: Near Deadwood, S.D., a small Canadian firm went bankrupt and left taxpayers a $40 million cleanup bill. At Montana’s Fort Belknap Indian Reservation, another bankrupt Canadian company stuck taxpayers with an estimated $33 million in cleanup costs. In southern Colorado, yet another bankrupt Canadian concern created a mess that will cost more than $200 million to clean up, while 17 miles of the Alamosa River were left devoid of fish and most other creatures for about eight years. In central Idaho, Hecla Mining Co.’s Grouse Creek mine, hailed as a marvel of modern mining when it opened in 1994, has slowly leaked cyanide into the ground and into a nearby creek. Near San Luis, Colo., Battle Mountain Gold’s self-proclaimed “environmentally friendly” mine experienced a large and unexpected buildup of cyanide within a year of opening. Near Whitehall, Mont., the Golden Sunlight mine, run by Placer Dome, a Canadian company, contaminated wells of two nearby ranchers. There’s a big difference between mines envisioned by Congress in 1872 and those operating today. Modern mines are far bigger, and many employ deadly cyanide to leach precious metals from rock. The leaching technique was used in small measure by miners in the early 1900s to draw gold and copper out of ore so low in mineral content that large-scale operators would have tossed it out as waste.

In the old days, leaching was done by misting cyanide over a barrel or large vat filled with crushed ore. The cyanide dissolved microscopic specks of gold from the rock, much as water dissolves sugar. As gold soared to $850 an ounce in the early 1980s, mining companies brought back the leaching technique in a big way, wringing more gold from long-closed mines and developing new ones where the ore had been considered too poor to bother. Miners still mix cyanide and water and slowly trickle it over piles of ore, but the piles are much bigger. Now they blast away entire mountains of rock, pile the ore in heaps the size of a football field and apply a river of cyanide, leaving behind hills of tailings and waste rock. Environmentalists cringe at the technique, not just because of the hazard of an accidental cyanide release, but also because of a long-term risk related to exposure of rock to the weather. The ore is often high in sulfides, and water passing through the rock and soil creates sulfuric acid, which in turn leaches poisonous heavy metals into runoff water, with iron in the rock turning streams an orange-red.

Forest Service, BLM decide

Environmental Protection Agency officials estimate that 40 percent of Western watersheds are affected by mining pollution. And sometimes EPA officials have advised against allowing a mine to open. But the EPA’s concerns are sometimes ignored since the ultimate go-ahead comes from the Forest Service or the BLM. The Grouse Creek mine in central Idaho, for example, won Forest Service approval even though the EPA warned that a strikingly beautiful high-elevation wetland valley would be destroyed. “Let the fun begin!!!!!” Forest Service mining engineer Pete Peters wrote in jest to a supervisor as he tried to figure out how to manage millions of gallons of muddy runoff water at the mine. Today, Peters acknowledges that he was unprepared for the enormity of his task of regulating the mine. “There’s no textbook. You have to hope you can stay ahead of it,” he said. “It was like nothing I’d ever dealt with.” The mine, leaking cyanide, closed after three years without making a profit. Signs posted by a nearby creek for a time warned, “Caution — do not drink this water.”

Mining industry officials acknowledge that there have been environmental problems, even with modern mines. But they say that the industry generally does a good job of policing itself, and that state regulators also keep an eye on miners. “The mining industry is not perfect, and mining has risks and it has impacts,” said Laura Skaer, director of the Northwest Mining Association. “Over the years, the industry has developed the practices and the techniques, coupled with regulations, to mitigate those impacts. It doesn’t mean there aren’t going to be accidents; that there isn’t going to be an occasional bad actor.” Accidents started to happen as soon as the Summitville mine opened in southwestern Colorado. Within six days, cyanide was leaking. The mine operator, Galactic Resources Ltd. of Canada, later went broke.

Galactic was one of a series of small mining companies, often financed through the loosely regulated Vancouver Stock Exchange, that rose to prominence during the mining boom before crashing in bankruptcy. Like other Canadian companies, it was allowed to mine on U.S. federal land even though Congress in 1872 specifically limited the privileges of the General Mining Law to “citizens of the United States and those who have declared their intention to become such.” The reason: In 1898, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that corporations have the same legal rights as people. So today, a Toronto-headquartered firm such as Barrick Gold Corp. can set up a subsidiary in Nevada and privatize nearly 1,950 acres for less than $10,000. Last year, Barrick hauled away nearly 2.5 million ounces of gold worth more than $600 million on the open market. “We have concluded, and the U.S. has concluded and many countries around the world have concluded that it is in their interest to provide an incentive to cause people to search for a mineral that otherwise isn’t know to exist in that ground,” said Pat Garver, Barrick’s head lawyer. Yet another Canadian firm, with offices in Spokane, Pegasus Gold, left three failing mines in Montana, including one that will cost taxpayers $33 million to clean up. Most Pegasus staff members kept working for the company as it reorganized, continuing to operate more profitable mines. Some even got bonuses.

Nothing for U.S. taxpayers

Not all critics of the 1872 law call for reform because of environmental damage. Some are galled by the fact that the law, breaking with tradition, allows miners to dig a fortune from public land without giving a share to the American citizens who own it. Europe’s royal families demanded a portion of all minerals taken from their New World colonies. And in the 18th century, Congress passed a law requiring a third of the profits from mines on federal lands go to the Treasury. “Even the early miners in the West followed local mineral laws modified from German and British traditions which required a portion of the minerals to be returned to the community,” said Carol Russell, mining specialist in the EPA’s Denver office. “However, it appears that in the rush of the gold rush, royalties were forgotten, and haven’t surfaced yet.” In 1920, Congress removed oil, natural gas and other minerals that could be used for fuel from the 1872 Mining Law. Instead, the government would lease the rights. And in 1977, Congress decreed that miners of coal on federal land would have to pay a royalty of 8 to 12.5 percent, and clean up after themselves. The government in the past decade has collected $11.08 billion from companies taking coal, oil, and natural gas, plus $35.8 billion in rents, bonuses, royalties and escrow payments for offshore oil and gas reserves.

Still, hard-rock miners pay nothing for the gold, silver, platinum, copper and other minerals they get. Walish, the manager of Cambior’s Top of the World project, joins many in the mining industry in warning, “If massive royalties are put on federal land, you’re going to see a lot less mining.” Critics are even more agitated about the mining companies’ ability to transform public land into private land for no more than $5 an acre — close to the fair market value for ranch and farmland in the West in 1872. Since 1964, more than 289,000 acres have been privatized, or patented, for mines. Congress has temporarily prevented additional land from being privatized, but applications already in the pipeline are eligible to continue with the process. About 73,000 acres could eventually be privatized this way. In 1872, Congress sold the land cheap because it wanted the West to be settled. That’s why a typical claim of 20 acres cost $100 — about three months’ rent in a Seattle boardinghouse. Now, critics ask, why should the government continue to sell public land for a pittance when the frontier is closed, and the West largely settled?

‘Why are they tearing it up?’

Years ago, a young man growing up in northern Arizona was surprised to see a big hole being scooped from the flanks of the picturesque San Francisco Peaks near his home. The mountains are considered sacred by the Hopi, the Navajo and 11 other tribes. “They started ripping the side of this mountain open, and I remember asking early on: ‘Who owns this land? And why are they tearing it up and carting it away?'” he recalled. Decades later, “it’s expanded into a gigantic scar on these sacred mountains. … One of the most unspeakably beautiful places in the Southwest is being carted away, truckload by truckload.”

The man is Bruce Babbitt, former Arizona governor and Interior secretary in the Clinton administration. For eight years, Babbitt administered the 1872 Mining Law. Babbitt hates the 1872 Mining Law. What was being mined near Flagstaff was pumice, a light volcanic rock. Today most of it is used to give denim that soft, “stone-washed” look. “It’s not like it’s being mined for some metal that’s necessary,” Babbitt said in an interview before leaving office. “It’s being mined to make blue jeans look old. It’s just a scandalous commentary on the Mining Law of 1872.” (The Los Angeles Times reported last week that Babbitt is helping The Hearst Corp., owner of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, broker a deal worth $200 million or more that will determine the fate of Hearst’s seaside ranch at San Simeon in central California.)

Babbitt never forgot the San Francisco Peaks, and last year the government agreed that federal taxpayers would give the mine’s operators $1 million to stop digging. He also worked hard to overhaul the law that allowed them to do it in the first place, calling it “a license to steal.” His case was bolstered by the General Accounting Office, the investigative arm of Congress, which issued numerous reports critical of the 1872 law, saying it “runs counter to other national resource policies” while allowing valuable land to be sold at nominal amounts. Facing stiff opposition from a Republican-controlled Congress, Democrat Babbitt switched gears in early 1997, pushing for more modest reforms through a rewrite of his agency’s own rules for administering the law.

Opponents in Congress moved to block even that reform. They ordered Babbitt to stall the rewrite of the rules until a panel appointed by the National Academy of Sciences could study the issue and report back. The NAS panel concluded that mine regulations “are generally well coordinated, although some changes are necessary.” It listed seven “regulatory gaps,” including “financial risks to the public and environmental risks to the land” because companies sometimes post inadequate bonds to pay for reclamation after mining ends. Likewise, the EPA’s inspector general concluded that “critical gaps” in bonding programs “could result in environmental problems and sizable cleanup costs for the federal taxpayers.”

These criticisms stemmed from a system that allowed local Forest Service and BLM officials to negotiate a financial guarantee with a mining company to cover cleanup costs. Those “guarantees” can prove uncollectible after a bankruptcy. Cleanup bonds posted by some miners were often inadequate to cover the true cost of fixing the environmental damage associated with huge modern mines. They also assumed the company would save money by doing much of the work itself, while bankrupt firms often simply abandon mines. Babbitt went further than the NAS panel suggested, though. The new regulations set minimum environmental standards for mines and, for the first time, gave federal land managers authority to deny a mining permit if it would cause “substantial irreparable harm … that cannot be effectively mitigated.”

As for reclamation bonds, the new rules assume a worst-case scenario: The company goes bankrupt, and the government has to take over. Some forms of bonds that have proven difficult to collect were forbidden. The rules were published in the Federal Register in November, and went into effect at 12:01 a.m. on Jan. 20 — just hours before George W. Bush was sworn in as president. The mining industry has characterized the rules as “burdensome, complex, counterproductive … onerous and misguided regulations rushed through during the waning days of the Clinton administration.” Jack Gerard of the National Mining Association said that “the Clinton administration took a sledgehammer to deal with a mosquito.”

Among those to challenge the rules in court were his association and the state of Nevada, home of most of America’s gold mines. Environmentalists, too, have been critical of the new regulations. Alan Septoff, legislative director of the Mineral Policy Center, said miners are still allowed to harm the environment, so long as they “effectively mitigate” the damage elsewhere. “Even though the stronger mining rule is monumentally better than the old rule, that’s a testament to the inadequacy of the old rule,” Septoff said. In March, Babbitt’s successor as U.S. Interior secretary, Gale Norton, ordered a reconsideration of the rules. Next month, the BLM is expected to issue a watered-down version of Babbitt’s rules or revert to old regulations adopted in the Carter administration. At the EPA, this prospect causes concern — particularly if rules on cleanup bonds are to be weakened. “The vast majority of these (mining Superfund) sites were historic sites, but in recent years we’re finding sites that are inadequately bonded, and the government is getting saddled with the cleanup costs,” said Nick Ceto, mining coordinator at the EPA’s Seattle office. “There are others that are coming up.”

STEP THREE : RATE FISCAL COMPETENCE

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB124580461065744913.html

http://reclaimdemocracy.org/corporate_welfare/

http://www.doingbusiness.org/economyrankings/

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/13/world/asia/13intel.html

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748704905604575027673196231564.html

Afghanistan to Delay Awarding Concessions for Mineral Deposits

by Matthew Rosenberg / January 27, 2010

Afghanistan plans to delay awarding concessions for a major iron ore deposit and sizeable oil and gas reserves as part of a broader effort to stamp out corruption, the country’s finance minister said. The move by Afghanistan could upend the plans of Total SA, Swiss-based Addax Petroleum Corp. and Canada-based Nations Petroleum Co., all of which were among the seven finalists selected last year for oil and gas blocks in the country’s northwest. Of particular concern, said Finance Minister Omar Zakhilwal in an interview Tuesday, is a major iron ore deposit in central Afghanistan that last year attracted bids from smaller Chinese and Indian companies. “We’ve put a hold onto to the bidding process; it will have to be re-bid,” he said.

Mr. Zakhilwal would not directly say whether he believed bidding for any of the projects – the iron ore deposit, the oil and gas reserves and scores of other smaller mineral deposits — had been marred by bribery, kickbacks or other forms of corruption. He spoke in general terms about the need to root out corruption and ensure Afghanistan gets the best deals when bringing in foreign firms to exploit its natural wealth. Afghanistan is rich in minerals and gemstones, with huge copper and iron ore deposits and reserves of emerald and rubies. Exploiting those reserves could help provide the country with much of the money it needs to wean itself from the massive infusions of foreign aid on which it new depends.

Putting the Afghan economy in order is one of the major issues to be addressed at a conference Thursday in London on Afghanistan’s future. Foreign ministers from 56 countries along with representatives from the United Nations and other international organizations involved in stabilizing Afghanistan are to attend, and European diplomats have in recent days said they are keen to hear Mr. Zakhilwal’s economic plans for the coming years. Mining could be a major economic contributor. But the Mines Ministry has long been considered among Afghanistan’s most corrupt government departments, and Western officials have repeatedly expressed reservations about the Afghan government awarding concessions for the country’s major mineral deposits, fearful that corrupt officials would hand contracts to bidders who pay the biggest bribes — not who are best suited to actually do the work. Mr. Zakhilwal said those concerns are shared by many inside the Afghan government, too. “I was among those who have been opposed to opening up new bids,” he said. “It was not just the issue of corruption – but that is a real issue. We also need to do a review of how contracts are awarded, what lessons we’ve learned, what kind of transparency is needed to make the next best step.” Mr. Zakhiwal that process is now underway with the appointment of a new minister, Wahidullah Sharani.

Still, he said there was no evidence of corruption in the awarding of the one major concession given out in recent years, a copper mine being set up by two Chinese firms, China Metallurgical Group and Jiangxi Copper Group. That project attracted bids from all over the world, and there have been persistent reports of bribes being paid to secure it. Mr. Zakhilwal termed those reports “rumors” and held up the deal – under which the companies agreed to build schools, clinics, markets, mosques and a power plant — as a model for how Afghanistan could award future concessions.

STEP FOUR : DISTRIBUTE

http://globalpolicy.org/home/211-development/48036-a-basic-income-program-in-otjivero.html

http://www.bignam.org/page5.html

History and background of the pilot project

At the end of 2006, the understanding in the BIG Coalition grew that the BIG campaign needs to be taken a step further by starting a pilot project of the BIG in Namibia. The background is that a pilot project might be able to concretely show that a BIG can work and will indeed have the predicted positive effects on poverty alleviation and economic development. Spearheaded by Bishop Kameeta this idea has been inspired by the concrete (or from a theological perspective “prophetic”) examples, like e.g. English medium schools or township clinics during the apartheid era. In fact, also more recently, this has happened with a project run by the Treatment Action Campaign and ‘Doctors without borders’ and the provincial government in Cape Town. They started a treatment project in a township in Cape Town at a time when it was said that a rollout of Antiretroviral (ARV) therapy is good but certainly not practical in a developing country. The pilot project was successful and has subsequently changed the opinion on ARV rollouts in developing countries. The BIG Coalition argues that while it is the ultimate goal to lobby Government to take up its responsibility to implement such a grant, the Coalition should lead by example. The BIG Coalition fundraised in order to pay a Basic Income Grant in one community. Thereby it set an example of redistributive justice through concrete action to help the poor, and to document what income security means in terms of poverty reduction and economic development. The BIG Coalition hence at the end of 2006 to implement a BIG pilot project. The BIG pilot project started in January 2008 and was the first of its kind, to concretely pilot an unconditionally universal income security project in a developing country. The BIG Coalition implemented a BIG in one Namibian community, namely Otjivero – Omitara settlement (about 1,000 people, some 100 km to the east of Windhoek) for a limited period of time (2 years, from January 2008–to December 2009) to practically prove that income security indeed works and that it has the desired effects.

EQUALLY

http://www.citizenpolicies.org/articles/worldpeace.html

http://www.citizenpolicies.org/articles/iraq.html

http://www.nytimes.com/2003/09/10/world/struggle-for-iraq-iraq-s-wealth-popular-idea-give-oil-money-people-rather-than.html

A Popular Idea: Give Oil Money to the People Rather Than the Despots

by John Tierney / September 10, 2003

Few Iraqis have heard of the ”resource curse,” the scholarly term for the economic and political miseries of countries with abundant natural resources. But in Tayeran Square, where hundreds of unemployed men sit on the sidewalk each morning hoping for a day’s work, they know how the curse works. ”Our country’s oil should have made us rich, but Saddam spent it all on his wars and his palaces,” said Sattar Abdula, who has not had a steady job in years. He proposed a simple solution instantly endorsed by the other men on the sidewalk: ”Divide the money equally. Give each Iraqi his share on the first day of every month.”

That is essentially the same idea in vogue among liberal foreign aid experts, conservative economists and a diverse group of political leaders in America and Iraq. The notion of diverting oil wealth directly to citizens, perhaps through annual payments like Alaska’s, has become that political rarity: a wonky idea with mass appeal, from the laborers in Tayeran Square to Iraq’s leaders. American officials have projected that a properly functioning oil industry in Iraq will generate $15 billion to $20 billion a year, enough to give every Iraqi adult roughly $1,000, which is half the annual salary of a middle-class worker.

No one suggests dispensing all of the money — and some say the government cannot afford to give up any of it — but there have been proposals to dispense a quarter or more. Leaders of the American occupying force have endorsed the oil-to-the-people concept and said recently that they plan to discuss it soon with the Iraqi Governing Council. The concept is also popular with some Kurdish politicians in the north and Shiite Muslim politicians in the south, who have complained for decades of being shortchanged by politicians in Baghdad. ”Giving the money directly to the people is a splendid idea,” said one member of the Governing Council, Abdul Zahra Othman Muhammad, a Shiite from Basra who leads the Islamic Dawa party. ”In the past the oil revenue was used to promote dictatorship and discriminate against people outside the capital. We need to start being fair to people in the provinces.”

When oil wealth is controlled by politicians in the capital, one result tends to be the resource curse documented in the last decade in academic works with titles like ”The Paradox of Plenty,” ”Does Oil Hinder Democracy?” and ”Does Mother Nature Corrupt?” Among the many researchers have been Jeffrey Sachs of Columbia University and Paul Collier of Oxford University, both economists, and Michael L. Ross, a political scientist at the University of California at Los Angeles. The studies have shown that resource-rich countries in the Middle East, Africa and Latin America are exceptionally prone to authoritarian rule, slow economic growth and high rates of poverty, corruption and violent conflict.

Besides financing large armies to fight ruinous wars with neighbors, as in Iraq and Iran, oil wealth sometimes leads to civil wars over the sharing of the proceeds, as in Sudan and Congo. ”Governments tend to use mineral revenues differently from the revenues they get from taxpayers,” said Dr. Ross, who found an inverse relationship between natural resources and democracy. ”They spend more of it on corruption, the military and patronage, and less of it on basic public services. Oil-rich governments don’t need to tax their citizens, and taxation forces governments to become more representative and more effective.”

On April 9, the day Saddam Hussein’s statue was toppled in Firdos Square, a plan to end Iraq’s resource curse was published by Steven C. Clemons, executive vice president of the New America Foundation, a centrist research group. He proposed using 40 percent of Iraq’s oil revenue to create a permanent trust fund like the one in Alaska, which has been accumulating oil revenue for two decades. That capital is invested and each year a share of the income is distributed — more than $1,500 to each Alaskan in recent years. ”A fund like Alaska’s is the best way to prevent one kleptocracy from succeeding another in Iraq,” Mr. Clemons said. ”It would go a long way to curbing the cynical belief that Americans want Iraqi oil for themselves, and it would give more Iraqis a stake in the success of their new country. It would be the equivalent of redistributing land to Japanese farmers after World War II, which was the single most important democratizing reform during the American occupation.”

In America, Mr. Clemons’s idea was quickly embraced by many foreign aid experts, editorial writers, Bush administration officials and politicians of both parties. Some experts, though, have faulted the trust fund, saying it would be expensive to administer and would pay out small dividends at first, perhaps only $20 per Iraqi adult, until more capital was amassed. As an alternative, some have suggested skipping the individual payments in the early years and dedicating the money to economic development or social programs. Money could be invested in a long-term pension program, as Norway does with some of its oil revenue. Another alternative would be to make bigger payments up front by giving the money directly to citizens instead of putting it into a trust fund. Thomas I. Palley, an economist at the Open Society Institute, proposed dividing a quarter of the oil revenue each year among all adults in Iraq. That could amount to $250 per adult, assuming that the administration’s hopes for oil production prove accurate.

Oil companies would not be directly affected by an oil fund, since they would be paying the same taxes and fees no matter what the government did with the money. But they could benefit indirectly if citizens eager for higher payments pressed the government to increase production and open the books to outside auditors. ”The oil industry likes working in countries with dedicated oil funds and transparent accounting, because there’s less loose money to corrupt the government,” said Robin West, chairman of PFC Energy, an American consulting firm to the oil industry. ”Corruption is bad for business,” Mr. West said, ”because it creates instability. In places like Alaska and Norway, people support the oil industry because they see the benefits. In places like Nigeria, they see all this wealth that doesn’t benefit them, and they start seizing oil terminals.” Iraq’s civilian administrator, L. Paul Bremer III, has praised the idea of sharing ”Iraq’s blessings among its people,” and suggested that the Governing Council consider some kind of oil fund. Iraqi politicians, of course, have no trouble understanding the appeal of handing out checks to voters.

The chief argument against an oil fund is that Iraq’s government cannot afford to part with any oil revenue for the foreseeable future. It faces a large budget deficit this year, and sabotage to the oil industry has reduced oil production far below projections. ”There isn’t that much money now, and we need every penny for rebuilding the country,” said Adnan Pachachi, a member of the Governing Council and former foreign minister of Iraq. ”Giving away money would be politically popular,” he said, ”but we should not gain popularity at the expense of the long-range interests of the country. By giving away the money you may sacrifice building more schools and hospitals.”

Some have suggested letting the government keep all of the revenue until oil production increases well beyond current levels, then putting the extra money into a fund. But the oil-to-the-people advocates say that now is the time to at least establish the framework for the fund, before a permanent government gets addicted to the revenue. If experience is any guide, that government would probably not be devoting the money to schools and hospitals. ”There is a direct proportional relationship between bad government and oil revenue,” said Ahmad Chalabi, the current chairman of the Governing Council and the leader of the Iraqi National Congress. ”If the government performs well or badly it doesn’t matter, because the oil revenue continues to flow. The government will use the oil revenue to cover up mistakes.”

Mr. Chalabi pointed to a precedent: a trust fund that existed in Iraq during the 1950’s, when part of the oil revenue went not to the government’s budget but to a development fund whose disbursements were directed by Iraqi and foreign overseers. ”The fund worked very well,” he said. ”Iraq’s economy in the 1950’s and 1960’s was relatively good.” Back then, Mr. Chalabi said, oil revenue was a relative pittance, adding up to less than $10 billion in the four decades preceding the Baath Party’s rise to power in the late 1960’s. But then came the resource curse. During a single decade, the 1980’s, Iraq’s oil revenue amounted to more than $100 billion. ”What happened to it?” Mr. Chalabi asked. ”Iraq was a much better country in every aspect before it got that money.”

LIKE THEY DO in ALASKA

http://www.apfc.org/home/Content/dividend/dividend.cfm

http://www.apfc.org/home/Content/aboutAPFC/lawIndex.cfm

http://www.pfd.alaska.gov/faqs/index.aspx

http://www.adn.com/2010/06/10/1317732/plan-puts-energy-future-in-alaskan.html

http://iraqdividend.com/alaska_dividend/

Hammond advocates dividend for Iraq

by Sam Bishop / February 22, 2004

Former Alaska Gov. Jay Hammond said Saturday that President George Bush should make an Alaska-like dividend for Iraqis a central element of his re-election campaign. Hammond made the remark after delivering a history and defense of the Alaska Permanent Fund dividend to the annual conference of the U.S. Basic Income Guarantee Network. The organization wants governments to offer all citizens, regardless of their own means, enough money to live. It says the Alaska dividend, which Hammond helped create while governor, is “the only example of an existing basic income guarantee in the world today.” Hammond, 81, warmed up the audience of about 100 at the Capitol Hyatt Hotel by reflecting on the U.S. BIG Network’s warm praise and on other accolades received in recent years. Honors have recently come from such diverse sources as sportsmen, environmentalists and developers, he marveled. After recently receiving an honor from his old nemesis, the Teamsters Union, he said he wondered “what can I expect next … an award for my contributions to public morality, co-sponsored by Jerry Falwell and Larry Flynt?” Hammond has been on a sort of moral crusade recently as he has perceived a growing threat to the dividend program. Earlier this month Hammond crashed the Conference of Alaskans, a 55-member group Gov. Frank Murkowski convened to talk about the permanent fund’s future, and diverted the participants into a discussion of income taxes as well. Saturday, Hammond recited a detailed history of his dividend advocacy, starting with his attempts in the 1960s as mayor of the Bristol Bay Borough to capture some of the salmon dollars that “hemorrhaged” out of that region. He reviewed his advocacy of a pre-permanent fund idea called “Alaska Inc.” in the mid-1970s as a Republican governor, then used the current Alaska dividend debate as a segue into the international arena.

“Without a permanent fund dividend program,” Hammond said. “Alaska will face the same fate as Nigeria.” There, the World Bank estimates that $296 billion flowed in and out of the government’s treasury during its oil boom, “leaving them worse off than they were before,” Hammond said. The Economist magazine appropriately called such mismanaged oil wealth, “the devil’s excrement,” Hammond said. The pattern has been repeated around the globe where countries have come into an oil windfall, he said. “Absent something like our dividend program and ensuing public interest, those windfalls simply inflated a grab bag for special interests. Once deflated, the average citizen was left holding that empty bag,” Hammond said. “Iraq is but the latest example.” He noted that Alaska Sen. Ted Stevens, at his request, proposed to President Bush that the U.S. push for an Alaska-style dividend program after the Iraq war. “Ted, incidentally, wrote me back after that and said ‘I talked to the president. He’s very much interested. Stay tuned,'” Hammond said.

He said he hasn’t heard much since, but intends to seek an audience with the president to push the idea. Hammond noted that he met the president’s father, former President George Bush, years ago in Alaska before the elder Bush was well known nationally. The elder Bush helped with his fund-raising and even wrote a blurb for his autobiography, Hammond noted. “I owe George Junior at least this–to convey to him how he could make this the centerpiece of his national campaign, thereby hopefully propelling the other candidates into the same arena to compete to see who can do more to propel or promote the concept in Third World countries, Iraq or wherever,” Hammond said. “If George Bush is out front, I think he’ll capture a lot of attention. I think his opposition certainly are not going to oppose it. “What better way to induce a capitalistic, democratic mindset among Iraqis? Far better than a few privileged kleptocrats living in opulent splendor while others grovel in squalor,” Hammond said.

To give some credentials to the idea, Hammond quoted 2002 Nobel-laureate in economics Vernon Smith, a professor from George Mason University in Arlington, Va., who spent much of 2003 at the University of Alaska Anchorage. “This is the time and Iraq is the place to create an economic system embodying the revolutionary principle that people’s assets belong directly to the people and can be managed to further individual benefits and free choice without intermediate government ownership,” Hammond quoted Smith as saying. Brazilian Sen. Eduardo Suplicy, who also spoke at the U.S. BIG Network conference, read a portion of a letter he wrote recently to the U.S. administrator in Iraq, Paul Bremer, also advocating an Alaska-style dividend plan. The idea has been endorsed by a variety of people, including a top United Nations official killed in a bombing last summer, Suplicy said.

In Iraq, the economist Smith recommended following Alaska’s precedent but avoiding Alaska’s mistakes, Hammond noted. Those mistakes were two-fold: Not putting all public resource wealth into the fund, and not reserving the income solely for dividends unless approved by a vote of the people. “Since this is precisely what I wanted but failed to do first with Bristol Bay Inc. with fish and later with oil and Alaska Inc., I find that comment vindicating,” Hammond said. “The following, however, I find truly rapturous. “Beware of giving governments drawing rights on the value of public assets,” Hammond quoted Smith as saying. “Public resources should belong directly to the public through mechanisms such as Alaska’s permanent fund … It is a model governments all over the world would be well-advised to copy.”

In questions after his speech, though, Hammond sensed that he and some of his association audience members may differ on a fundamental. Hammond’s pro-dividend philosophy rests upon the public ownership of the resources feeding the Alaska Permanent Fund. So when asked whether he thought an income tax should also be used to bolster the dividend, he balked. “People resent having their hard-earned income taken from them and redistributed,” he said. He said he sympathizes with that idea and on that score may differ from the ideas advocated by the U.S. BIG Network, he said. “Our program doesn’t contemplate taking income made by the public.” So what happens to those residents of places in the world unlucky enough to have neither “salmon nor oil,” another member of the audience asked. Hammond said he didn’t really know. He said he had recently been intrigued by proposals to auction rights to pollute the air, as a publicly owned resource, and distribute the proceeds as dividends.

ENDORSED by MARTIN LUTHER KING Jr, BERTRAND RUSSELL, MILTON FRIEDMAN…

http://www.progress.org/dividend/cdking.html

http://www.commercialappeal.com/news/2010/jan/18/king-focused-on-ending-poverty/

‘Guaranteed income’ plan finds support

by Bartholomew Sullivan / January 18, 2010

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. wrote: “I am now convinced that the simplest approach will prove to be the most effective — the solution to poverty is to abolish it directly by a now widely discussed measure: the guaranteed income.”

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. had another dream: the guaranteed income. Those careful about his legacy say the $120 million monument to him that’s finally nearing construction on the National Mall is all well and good. But as the nation commemorates King’s 81st birthday today, they say he should best be remembered for his career-long focus on the poor. A year before his 1968 death in Memphis, in his “Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community,” King wrote: “I am now convinced that the simplest solution to poverty is to abolish it directly by a now widely discussed measure: the guaranteed income.”

The idea was to guarantee that no one lived in poverty by having the government provide a financial floor, pegged to median — not low — incomes, beneath which no one could fall. King talked about the psychological benefits of a widespread sense of “economic security.” Economists John Kenneth Galbraith, Paul Samuelson and Milton Friedman endorsed the idea of guaranteed incomes, as did Lyndon Johnson’s Labor Secretary and later New York Sen. Daniel P. Moynihan. Advocating the proposal was the official debate resolution for public high schools in 1973. It was a mainstream idea that has since faded from view.

But a movement to spur a guaranteed income plan is reawakening in academic and anti-poverty circles as the nation looks at 15.3 million people seeking work and the prospect of large-scale and long-term unemployment. The Basic Income Guarantee movement (USBIG.net) is based on the belief that increased mechanization and labor efficiencies, coupled with the export of industrial and manufacturing jobs to low-wage countries, means there just isn’t enough work available. Once robots can understand speech, even more jobs in the service industries will disappear, they say.

And yet people will still need to live even without work. Advocates say a redistribution of some anti-poverty program funding for direct subsidization of adequate incomes would solve the poverty problem while stimulating consumption. University of Tennessee-Knoxville sociology professor Harry F. Dahms, a member of the U.S. Basic Income Guarantee Network, said when he talks about the idea in the South “audiences seem rather baffled, first, that such an idea even exists.” Their second response is surprise “that some people would entertain it seriously.”

In a class on social justice and public policy, Dahms, originally from Germany, discusses guaranteed incomes as a way for the work force to take advantage of growing efficiencies by having more people work fewer hours. In Memphis, efforts to enact a living wage for Shelby County and city employees and contractors were a step in the direction of raising the income bar. But Rebekah Jordan Gienapp, director of the Workers Interfaith Network, said King called for raising the minimum wage to a level that could raise working people out of poverty. She noted that, adjusted for inflation, it’s lower now than in 1968.

Tennessee and Mississippi don’t have state minimum wage laws and the minimum in Arkansas is lower than the current federal minimum wage of $7.25 per hour. “What does that tell us about how we’ve really, in a lot of ways, moved backwards since the civil rights movement in some of these economic ways?” she asks. “Particularly on Dr. King’s birthday, he tends to be held up as just someone who advocated diversity or integration, but his message was much broader and more radical than that …”

Supporters of a guaranteed income acknowledge the solution sounds radical but point to the subsidy every citizen of Alaska receives each year from the state’s oil revenue. The share-the-wealth program in one of the most Republican-leaning states is so popular that efforts to repeal it have failed. Congress actually considered a slimmed-down variant of a guaranteed income plan when U.S. Rep. Bob Filner, D-Calif., proposed the Tax Cuts for the Rest of Us Act in 2006 in response to Bush tax cuts for upper-income taxpayers. It would have made the standard income tax deduction into a refundable tax credit.

BASICS

http://www.bepress.com/bis/

http://www.statemaster.com/encyclopedia/Guaranteed-minimum-income

Basic income

Main article: Basic income

A basic income is granted independent of other income (including salaries) and wealth, with no other requirement than citizenship. This is a special case of GMI, based on additional ideologies and/or goals. While most modern countries have some form of guaranteed minimum income, a basic income is rare.

Examples of implementation

Portugal is by far the closest a country has come to actually having fully implemented such a system. This is because the Portuguese government made a guaranteed minimum income a legally enshrined right for the entire population in 1997. The policy remains at present. However, the country’s income security policy is rather residualist, with an amount guaranteed well below the poverty line, and other income security policies such as the minimum wage are thus still in place as a consequence. The system also forces participants to attend social integration sessions.

The U.S. State of Alaska has a system which guarantees each citizen a share of the state’s oil revenues (see Alaska Permanent Fund Dividend). The city of Dauphin, Manitoba, Canada had an experimental guaranteed annual income program (“Mincome”) in the 1970s.[1] Many other countries have political parties that advocate such a system, such as the Green Party of Canada, Green Party of England and Wales, the Canadian Action Party, the Anarchist Pogo Party of Germany, the Danish Minority Party, Vivant (Belgium), both the Scottish Green Party and recently the Scottish National Party, and the New Zealand Democratic Party.

In 1972, members of the American Democratic Party wrote a proposal for a GMI into their official platform. However, that particular plank, along with numerous others, was removed following the landslide defeat of Senator George McGovern, the party’s candidate in that year’s presidential election. One proposed method of offsetting the cost to the Treasury of this tax expenditure lies in its coupling with a flat tax, a type of federal income tax in which all taxpayers are subject to a single tax rate. The current model of progressive income taxes used throughout the western world could be eliminated, but the system would still be progressive, since those at the lower end of the wage scale would pay less in taxes than they would receive in guaranteed income. For the most wealthy members of society the few thousand dollars of the guaranteed income would only make a small dent in the taxes they have to pay. Also, the USA has the Earned income tax credit for low-income taxpayers. The citizen’s dividend is a similar concept, but the payment made to individuals is based upon the revenues that the government can collect from leasing and selling natural resources (such a dividend in fact exists in the state of Alaska).

Advocates

Modern advocates include Hans-Werner Sinn (Germany) and Ayşe Buğra (Turkey). Other advocates are winners of the Nobel Prize in Economics, including Paul Samuelson, James Tobin, Herbert Simon, Friedrich Hayek, James Meade, Robert Solow, and, depending on how one regards his negative income tax proposal, Milton Friedman. In his final book Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community? (1967) Martin Luther King Jr. wrote[2] “I am now convinced that the simplest approach will prove to be the most effective — the solution to poverty is to abolish it directly by a now widely discussed measure: the guaranteed income.” – from the chapter entitled “Where We Are Going”

Funding

Many different sources of funding have been suggested for a guaranteed minimum income:

Income taxes

Sales taxes

Capital gains taxes

Inheritance taxes

Wealth taxes, e.g. property tax

Luxury taxes

Elimination of current income support programs and tax deductions

Repayment of the grant at death or retirement

Land and natural resource taxes

Pollution taxes

Fees from government created monopolies (such as the broadcast spectrum and utilities)

Collective resource ownership

Universal stock ownership

A National Mutual Fund

Money creation or seignorage

Tariffs, the lottery, or sin taxes

Technology Taxes

Tobin Tax

UNIVERSAL BASIC INCOME (UBI)

http://www.globalincome.org/English/Earth-Dividend.html

http://www.cceia.org/resources/ethics_online/0019.html

http://ipsnews.net/news.asp?idnews=46179

http://www.basicincome.qut.edu.au/aboutbi/history.jsp

http://ubi.wairaka.net/

http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/social-minimum/

http://dieoff.org/page152.htm

http://www.bostonreview.net/BR25.5/vanparijs.html

by Philippe Van Parijs

Entering the new millennium, I submit for discussion a proposal for the improvement of the human condition: namely, that everyone should be paid a universal basic income (UBI), at a level sufficient for subsistence. In a world in which a child under five dies of malnutrition every two seconds, and close to a third of the planet’s population lives in a state of “extreme poverty” that often proves fatal, the global enactment of such a basic income proposal may seem wildly utopian. Readers may suspect it to be impossible even in the wealthiest of OECD nations.

Yet, in those nations, productivity, wealth, and national incomes have advanced sufficiently far to support an adequate UBI. And if enacted, a basic income would serve as a powerful instrument of social justice: it would promote real freedom for all by providing the material resources that people need to pursue their aims. At the same time, it would help to solve the policy dilemmas of poverty and unemployment, and serve ideals associated with both the feminist and green movements. So I will argue.

I am convinced, along with many others in Europe, that–far from being utopian–a UBI makes common sense in the current context of the European Union.1 As Brazilian senator Eduardo Suplicy has argued, it is also relevant to less-developed countries–not only because it helps keep alive the remote promise of a high level of social solidarity without the perversity of high unemployment, but also because it can inspire and guide more modest immediate reforms.2 And if a UBI makes sense in Europe and in less developed countries, why should it not make equally good (or perhaps better) sense in North America?3 After all, the United States is the only country in the world in which a UBI is already in place: in 1999, the Alaska Permanent Fund paid each person of whatever age who had been living in Alaska for at least one year an annual UBI of $1,680. This payment admittedly falls far short of subsistence, but it has nonetheless become far from negligible two decades after its inception. Moreover, there was a public debate about UBI in the United States long before it started in Europe. In 1967, Nobel economist James Tobin published the first technical article on the subject, and a few years later, he convinced George McGovern to promote a UBI, then called “demogrant,” in his 1972 presidential campaign.4

To be sure, after this short public life the UBI has sunk into near-oblivion in North America. For good reasons? I believe not. There are many relevant differences between the United States and the European Union in terms of labor markets, educational systems, and ethnic make-up. But none of them makes the UBI intrinsically less appropriate for the United States than for the European Union. More important are the significant differences in the balance of political forces. In the United States, far more than in Europe, the political viability of a proposal is deeply affected by how much it caters to the tastes of wealthy campaign donors. This is bound to be a serious additional handicap for any proposal that aims to expand options for, and empower, the least wealthy. But let’s not turn necessity into virtue, and sacrifice justice in the name of increased political feasibility. When fighting to reduce the impact of economic inequalities on the political agenda, it is essential, in the United States as elsewhere, to propose, explore, and advocate ideas that are ethically compelling and make economic sense, even when their political feasibility remains uncertain. Sobered, cautioned, and strengthened by Europe’s debate of the last two decades, here is my modest contribution to this task.

UBI Defined

By universal basic income I mean an income paid by a government, at a uniform level and at regular intervals, to each adult member of society. The grant is paid, and its level is fixed, irrespective of whether the person is rich or poor, lives alone or with others, is willing to work or not. In most versions–certainly in mine–it is granted not only to citizens, but to all permanent residents. The UBI is called “basic” because it is something on which a person can safely count, a material foundation on which a life can firmly rest. Any other income–whether in cash or in kind, from work or savings, from the market or the state–can lawfully be added to it. On the other hand, nothing in the definition of UBI, as it is here understood, connects it to some notion of “basic needs.” A UBI, as defined, can fall short of or exceed what is regarded as necessary to a decent existence.