ION EXCHANGE MEMBRANES

https://rowow.net/methods

https://github.com/Rowow1/Open-sourced-off-the-shelf-ion-exchange-membrane

https://gofundme.com/f/semtech

by Robert Karas, Rowow LLC

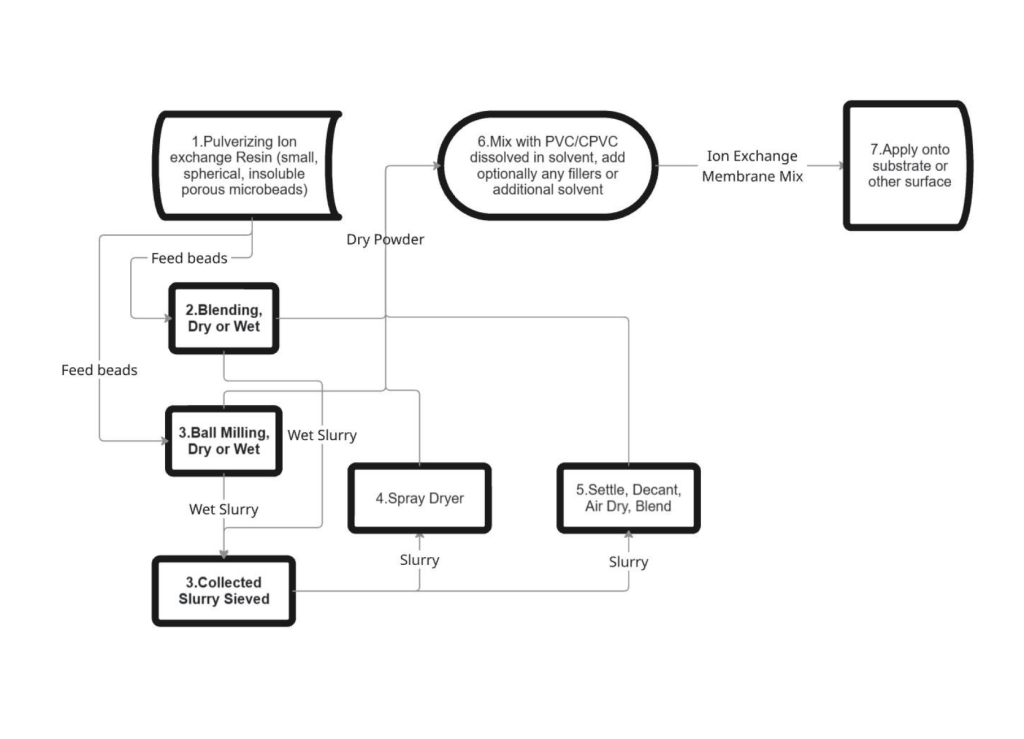

“…I’ve spent years developing a revolutionary ion exchange membrane using off-the-shelf ingredients like water softener resin and PVC cement. This homogeneous membrane is extremely affordable to make, yet it performs like commercial versions that cost much more. It’s durable in extreme conditions (pH 0, high ORP) and enables closed-loop processes with zero toxic waste.

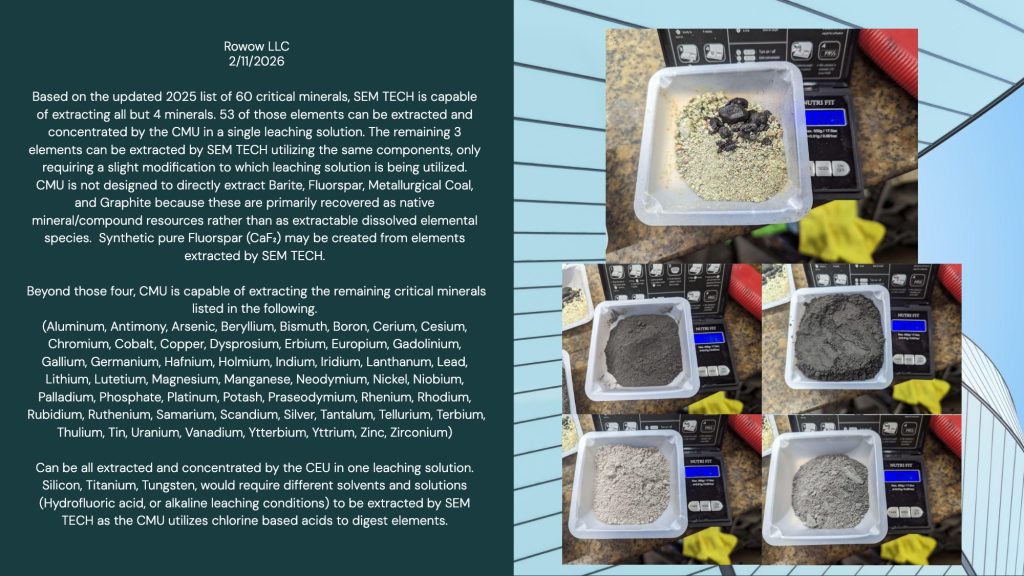

My primary focus right now is the mining industry: using it in Salt Electro Mining (SEM TECH) to extract precious metals and rare earths from ore, tailings, or e-waste while regenerating acids and oxidizers on-site. It cleans up legacy mine waste, recovers critical minerals domestically, and eliminates toxic ponds — real environmental impact. I’ve already filed a non-provisional patent (App. No. 19/531,984) and dedicated the technology to the public domain under CC0—anyone can build, use, or improve it freely. The full recipe, build guide, and files are open-sourced on GitHub.

To move from lab to real-world impact, I need your help scaling up: acquiring analytical equipment for validation and quality control. Every contribution accelerates adoption of sustainable, decentralized tech. Donors get updates, shoutouts, and for larger gifts, early prototype samples or custom consultations. My end goal is a location to mass produce and send out these units for $500,$1000 each. In addition to a proper analytical capabilities to develop further research and provide analytical analysis services which is desperately lacking for the nation. This isn’t just a membrane—it’s a path to cleaner mining, cheaper critical minerals, and a more sustainable planet. Join me in open-sourcing the future. Thank you for your support!”

with REDOX FLOW BATTERIES

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flow_battery

https://goldrefiningforum.com/open-source-salt-water-electro-mining-technology

Moderator: “Interesting video. How do you see this technology being useful to the refining industry? Specifically is this scaleable from a small test membrane up to a production setup and what form will these membranes return the values in. Simply put, do you have any descriptions or images of hardware to mount these membranes and details about what you are feeding the system and what you can recover. I went back and read some of your old posts and saw you were having issues recovering gold from solutions. How have you solved the problems with membrane technology and how are you proposing members here try this setup to either leach gold from ores or concentrates from secondary materials? Let’s explore this……”

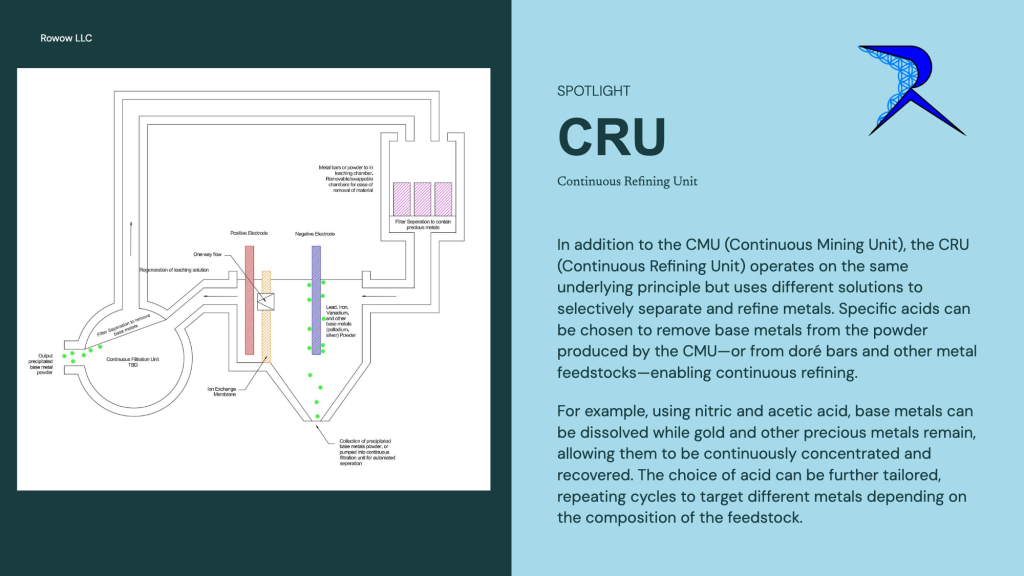

Robert Karas: “Yes its very much scalable. I have it as a 50 amp cell currently as a standard units. But my small scale testing are tiny cups at 1-2 amps. Any size you like to the thousands of amps. They can be wired in series also so technically can run directly off 120v with a bridge rectifier/capacitor setup. Each cell is 5-6 volts. For the refining industry we have some very unique and creative ideas, but the fundamental basic “CRU” (continuous refining unit) we have built and used basically uses different acids for its selective dissolving properties. For example, once you have a dory bar, powder, etc, you can run it through a CRU unit with acetic/nitric acid. This dissolves most base metals (lead iron copper etc) and leaves the precious metals behind (except silver/palladium).

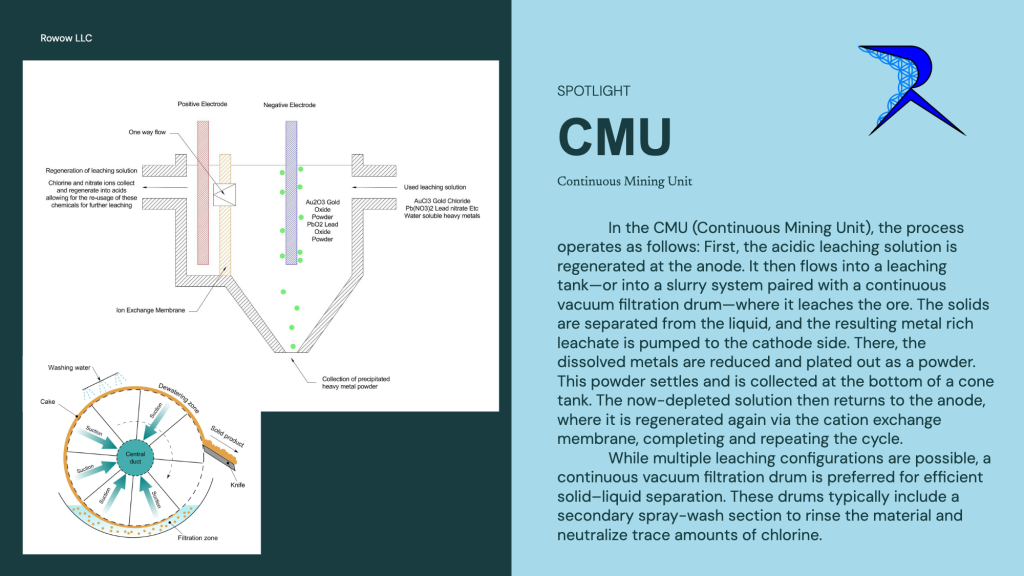

I already tested this on a bar that had vanadium and was a pain to dissolve in nitric. It just wouldn’t touch it. But through the CRU, I was able to continuously dissolve it completely automated. I didnt have to bother with fresh acids etc. The system regenerates the acid, leaches the material, pumps the leached solution to the negative side to plate off the metals, then the depleted solution flows back into the positive side to regenerate and repeat the cycle. This is all possible due to the ion exchange membrane between the negative and positive acting as a chemical diode, forcing reactions to go one way. Theres still room for improvement and optimization but as the technology stands it works and is economical. Mostly about scaling up to production, which costs alot of money, hopefully this grant will help me with that. I dedicated the past 2 years on this technology and have gotten so far on so little.

I have many units built and will attach pictures of my current design. It uses hot swappable electrodes and membranes, very easy to change out. The cost to refine per ton of material ends up around $50-400 a ton of iron. As a comparison, you would need 3.5 tons of nitric acid to dissolve that amount of iron. The cost benefits is immense. I have such a large range as my calculated costs are $50 per ton from a small test, but as a engineer I like to give lots of extra cushion just in case, which still makes it insanely game changing. Additionally with fire assay refining this has a huge benefit in being able to recover the lead into a precipitate powder for further reuse. I can go on and on. That post I made a long time ago about recovering the gold is how I ended up down this journey and developed this process.

Electro plating allowed me to recover but then I didn’t like the cost of nitric acid so was searching for a alternative oxidizer and found sodium chlorates, which is how PGMS are extracted from catalytic converters. My CMU (continuous mining unit) uses HCL and Sodium chlorate, both chemicals derived from saltwater and electricity, and can dissolve noble metals like rhodium which aqua regia wont touch, all at room temperature.Additionally if you look at my shorts I have tons of videos on the precipitate powder being produced from my system. I have a professional lab grade desktop xrf rigaku NED DE spectrometer verifying my results. (handheld XRF is a scam)”

Moderator: “You sound like an intelligent young man. But unfortunately you are not good at sales if that is your goal here. That is not made to be an insult, I’m 74 years old and I probably still suck at sales but I have learned to put technology into terms easily understood by clients, most of whom are not chemists. So let’s try to work this through for your system on a particular and very common type of scrap. Karat gold scrap. Do you digest the scrap to selectively dissolve out the non precious metals and what form does it dissolve from, bar, shot, or atomized particles? Is your system capable of high purity or strictly doré material? You mention continuous feed, how does that work? Is this concept similar to the porous cup methods where all impurities are contained on the anodic side. And while we are at it, silver refining, big now a days and the typical feed is above 90% silver with 7-10% copper and traces of Gold and Palladium. Is a membrane separation capable of enhancing electrolytic Silver refining? I hope you don’t see me as a rambling old man but while I understand the membrane portion I am struggling to see the mechanical system you put together to facilitate this whole thing. And I do see it as having great potential so I am looking for clarity.”

RK: “Firstly I greatly appreciate any advice and criticism! And yes I most definitely am not good at sales nor is that my intention currently. I am editing a video currently on using my technology on the mining industry, I am curious to hear your opinion on that. That one is more “sales” oriented. But this forum post is not self promotion, its just sharing of technology.

Answers:

>Do you digest the scrap to selectively dissolve out the non precious metals and what form does it dissolve from, bar, shot, or atomized particles?

Depending on which system used. I have currently two units, the CMU which uses HCL and Sodium Chlorate to dissolve pretty much everything. This is targeting for general extraction and recovery from ore, e waste, mining waste, etc. The intention is to concentrate down the heavy metals/rare earths/precious metals from rocks. This creates a metal powder.

The CRU uses more selective acids to separate out groups of metals for further refinement. It drastically reduced the amount of work, steps, and acid used in traditional refining and reduction.

>Is your system capable of high purity or strictly doré material?

The refining unit can produce higher grade concentrate material. Once it removes most base metals, the powder can be finally refined through electro winning or another method for high purity. But the goal with the refining unit is to convert a dore bar/etc with trace amount of gold, into something with only/mostly precious metals.You mention continuous feed, how does that work? Is this concept similar to the porous cup methods where all impurities are contained on the anodic side.

Correct, but in this case the “impurities” are actually the product, in the case of the refining unit with acetic acid/nitric, where all the base metals get dissolved, and gold, platinum, rhodium, etc gets left behind. Except for palladium and silver also gets moved with the base metals, but other chemicals can be used to separate those from the rest, all depends on what elements are present. For example we would use Hydrofluoric acid to separate lead from silver/etc. The entire philosophy is whatever traditional refining/chemical process people already use, can directly be applied with this technology to create a continuous method. A basket of the material would be submersed in the leaching side, dissolve the targeted elements, and the “impurity slime” would have undissolved metals left.

>And while we are at it, silver refining, big now a days and the typical feed is above 90% silver with 7-10% copper and traces of Gold and Palladium.

Is a membrane separation capable of enhancing electrolytic Silver refining?

This is a great example of the applications of this technology. Electro winning and many refining techniques in general are limited by what can be fed in. Many refiners are very strict with what materials they take in and work with. With this technology, it solves that. Mixed metal bars with many different elements can be ran through a couple of these continuous refining units to separate them into group metals. Just in one step, almost all base metals can be removed from gold. If there’s platinum then yes you don’t have “pure gold”, but its way easier to refine and separate gold and platinum, than a bar with lead, vanadium, and 15 other metals. Getting you a material thats 90% silver, or 90% gold etc, for final refining. We do have the intentions of creating a system that can output pure metal of each element in a single step but thats for further research.

You are not whats so over! I am very happy for your questions and they are very wise questions. Alot of people I present this to don’t get into the detail you are here. I will attach a diagram to help you understand the process. Apologies I missed alot of information, theres so much to discuss about. I have some of it on my website and the rest on my youtube, but theres just so much information and potential I don’t know where to start. But if you ask anything ill be glad to answer. Attached is a diagram example of the continuous refining unit, and the continuous mining unit. Again theres alot of information to share, for example on the continuous refining unit lead will plate off on both positive and negative electrodes, so a continuous filtration unit is needed after the positive electrode. Lots of little things like that will confuse things though so I am trying to keep it simple.

[Forum Member]: I have been experimenting several times to regenerate my used dirty sulfuric acid by creating copper sulfate, purifying by crystallization and electro-wining the copper and sulfuric back. I’ve tried a clay pot ion membrane, but that cracked in time, it does seem to work. very interested in the membrane and the costs. I might just try a lead car battery anode bag to hold my lead anode in to keep the lead sulfate and oxide out of the acid.

RK: Yes so this membrane recipe would exactly solve that! I love your approach for a clay pot ion membrane. That is the most common done and definitely can be finicky. Biggest issue is their high resistance, so you end up running at like 12 volts. With electro chemistry reactions are driven by current, not voltage. So higher voltage simply means more waste. And at 12v over 90% is waste which ends up as heat. With my membranes you can easily operate at 3-5 volts. I wish I could disclose the recipe now but I hope you can wait a few more months for the results on these grants (first one is march, second is july). But that is exactly what my technology does and solves. But its so easy to manufacture, apply, work with, and most importantly cheap. Otherwise if there’s anyone interested in sponsoring or helping with this technology I would greatly appreciate it. My goal is scaling up and final research. It works and has been proven in real life environments for months. Its mostly about scaling up now. There are some things especially with the CMU that I would like to do like adding a vacuum filtration unit to test fully continuous long term operation as I’m currently doing batch leaching ore (which is annoying as the ore turns into clay and doesn’t let leaching to seep through). So if anyone has a poly propylene or acid resistant vacuum filtration drum please message me! Otherwise they are $25,000 from China which I don’t have funds for.

Moderator: I watched your video’s and I see the promise. Let me provide for you a specific application which can commercially benefit a lot of electrolytic silver refiners. One of the issues with refining Silver from secondary sources comes from refining sterling Silver electrolytically. As the copper builds up it fouls the solution. Could this silver nitrate, copper nitrate solution use this membrane technology to regenerate nitric from the solution, leave Silver nitrate in solution and remove mostly Copper but other trace base metals from solution as a metallic fraction. I would assume a system of this type will be scalable based on membrane size. How would your system approach this challenge to provide an electrolyte that is essentially perpetually re-usable working in concert with a typical electrolytic Silver cell.

RK: I greatly appreciate the feedback! And yes most definitely this process would solve that. Copper nitrate would be split apart and only allows copper ions which are cations, to pass through a cation membrane and plate off on the negative side. Additionally I looked it up and copper has a lower reduction voltage than silver. So we could just run the cell at a specific voltage and especially since we are only concerned about a slow build up of copper ions we don’t care about mass electro plating off alot of material at once. That ensures the silver wont be plated off at all. Apologies I got that mixed up! The copper would still be plated off but as for the silver transitioning I’m not sure how much would cross over and mostly depends on how much is in the solution in the first place. Could you give more details on that? How this problem occurs and what concentration of copper occurs to silver that its a issue? Potentially we could have a copper only solution in the cation and running at a slow enough controlled current where only a controlled amount of copper gets transitioned through. Kinda like a refining cell but for copper. Or just do occasional cell purges to force out most of the dissolved metals. A few methods possible but would need testing. In the future I have some ideas on a completely selective refining system where we have selective ionic liquids or modify our membranes with certain selective ionic resins to allow for selective transfer but I don’t have funds to experiment with that currently and that definetly is very advanced research and currently just theoretical. I really appreciate this thought exercise, definitely very huge application! Another demonstration how this technology has large implications on basically every industry…

Moderator: Could your company market a system like this capable of “cleaning” something in the range of 50 gallons per day running continuously 24/7? And just a ballpark what would this system cost?

RK: yes. that would be a very small unit. My current “standard” units are at 50 amp capacity, which 50 gallons is easy to process. Most definitely even within a hour (depending on electrolyte/concentration/etc. This can easily be accurately calculated based off molar ratio/concentration, reduction electrons requires and its corresponding amperage. Like I did in the Iron Video [see above]. I’m estimating this to cost less than $200-500 in material for each electrolysis unit at mass production. Of course i’m in the prototype stage and prices are much higher. Just for materials/labor and is near $700-1000 (just the chemical pump is $150…). They are simple and easy to construct, but building something custom is definitely a different thing to mass production… Additionally I’m doing additional research and there’s certain aspects like the positive electrodes (making glassy carbon or lead dioxide in house rather than relying on graphite) and other parts that need a bit of upfront cost to develop and be able to scale up and get into the mass production stage. My goal was to sell a full system where you simply fill up, plug and play refining system based off my acetic acid/nitric to separate the base metals from gold in a single step. These units would be $5,000-10,000 range to cover the research costs associated and further development. These units can be utilized in different configurations or solutions for other applications though.

I was looking at commercial silver refining cells which cost $30,000 for their base models which I found absurd. I am curious what you think about the prices, especially the temporary early stage (5-10k) prices with the increased cost to help assist with funding further development. I definitely agree the silver refining cell is the easiest thing to start with. Simply removing the need of a positive electrode as the material being refined is the electrode is a huge help. Not sure how that market looks and its demand. There’s many avenues not sure what to prioritize. This morning just had a call with a guy regarding e waste potential. But if you want I can build a test cell and process some material to prove to you that this works. I’m very quick with making these cells and can get it done within a few days once I have the material to work with.

Moderator: Further thoughts along the silver cell logic when determining if the cost is justified. The nitric acid is best if maintained at 7 g/l but as Copper consumes 3.4 times the nitric acid to dissolve in the Silver cell this drives the nitric acid content down, requiring nitric additions to maintain the Silver concentration. If a membrane system is utilized will it return the nitrate ions from the deposition of copper back to the electrolyte to regenerate the solution? This could eliminate or greatly minimize the need to make more new electrolyte as well as to recover the Silver from spent electrolyte. A typical cell runs feedstock with 7.5 to 10% copper so on a small 3000 oz per week Silver cell removal of 300 oz a week of copper will keep the copper well below the range where it will co-deposit. The manufacturers of these cells claim they will process material as high as 20% Copper, which is true but the solution maintenance is huge. This technology could be sized to efficiently process Silver copper alloys and still operate efficiently. If a system can be tailored to meet these criterion, the savings in chemistry, labor and waste treatment will reduce the investment making a system more attractive. Having just read what I posted I want to say I have no affiliation with this company however I can recognize the great potential.

RK: The nitric not only would be regenerated but any lost nitric (n2 /any other losses) can be created from fertilizer, aka sodium nitrate. This would be done with a anion membrane. Sodium nitrate on the negative side, anion membrane, positive electrode/solution having the silver solution pumped through it. The nitric concentration can be measured with a EC/Ph meter or some other sensors, and the process can be done completely automated. As the electrical conductivity/concentration drops, this secondary cell running with the same solution can electrolyze in nitric acid. This is a very well known method with poor chemists in europe where nitric acid is banned so they have to figure out how to make it themselves. usually they use a clay pot as a ion exchange membrane but its veyr inefficient and high resistivity and no selectivity. So not only can I regenerate the nitric acid but I can produce fresh/pure nitric acid from scratch.

https://patents.google.com/patent/CN103866344A/en

Most refiners of silver target material that is 80% silver as you say. But with this technology I can economically refine silver in the sub percentage concentration.

Member 2: Great stuff. Be interesting to try on sulphide ore.

RK: I have used it successfully on high sulfide ore. It works though definitely is impacted by the sulfide. With batch processing if too much is added at once then it takes too long to “burn off” the sulfides and start being able to bleach. This should easily be solved in a continuous leaching process where little can be added at a time to fully react and stabilize the bleaching conditions

M2: I like the way you build stuff. That is cool. Have you checked the potential of that cell and the potential energy savings of just close looping it? Little slower but highly selective results. Bonus is no electricity bill. Could the process generate sulphuric acid as a beneficial by product? Yes. But a previously processed iron sacrifice would be needed to initiate this transition

RK: Yes ion exchange membranes are used to make sulfuric acid. In fact many hobby chemists where sulfuric acid and nitric acid is banned use clay pots as a ion exchange membrane to produce it at home from gypsum and sodium nitrate.

M2: Guess they don’t have any good ore instead. Hate to state the obvious mate. But I like you and I trust your curiosity. What happens when you short circuit a battery/cell ?

RK: Depends on whats dissolved. But the chemicals would react back with eachother. So for example if you have sodium hydroxide on one side and hcl on another, the sodium ions would transfer back and react with the hcl. This is called a “Sodium chloride (NaCl) redox flow battery”. You can actually regenerate power and charge/discard the chemical entropy between the two solutions. Theres many different solutions you can use and each one has their own benefits and downsides.

My favorite is a ferric chloride flow battery which can be made with scrap steel, some hcl. It was actually my first ever ion exchange membrane and ill upload a picture of me making a cell and powering a led light bulb with it. These 4 cups had 1ah of capacity at 4v. I ran it through a 18650 cell capacity tester. Redox flow batteries typically have half the energy density to lithium. So itll be twice as heavy for the same amount of energy stored. Thats isn’t a issue for grid storage and my vision was for heavy equipment as heavy equipment need to be… heavy… and typically have counterweights…”

PREVIOUSLY

SEAWATER LITHIUM MINING

https://spectrevision.net/2021/11/18/seawater-lithium-mining/

OSMOTIC POWER

https://spectrevision.net/2017/03/10/osmotic-power/

JUST ADD SALTWATER

https://spectrevision.net/2015/08/07/just-add-saltwater/