HOW to NOT MAKE WINE

https://grapecollective.com/how-to-not-make-wine

https://vinepair.com/articles/prohibition-ratification-state-map

https://vinepair.com/wine-blog/how-wine-bricks-saved-the-u-s-wine-industry-during-prohibition/

How Wine Bricks Saved The U.S. Wine Industry During Prohibition<

by Adam Teeter / August 24, 2015

“When Prohibition finally went into effect on January 16, 1920, those who owned American vineyards for the sole purpose of turning those grapes into wine faced a dilemma: tear up the vines and plant something else, or try and find a way to still make a profit from the grapes with the hope that ban on booze didn’t last very long. This conundrum was especially felt among the vintners of the Napa Valley, who by 1920 were already making a good portion of America’s wine.

Here was the problem: if these winemakers tore up their vines in search of other profits only to see Prohibition overturned a few years later, if they replanted, it could take up to ten years for those vines to start producing the kind of quality fruit they were currently producing. Some vineyard owners just couldn’t risk it, and as soon as Prohibition was passed, they tore up their vineyards and planted orchards. But those winemakers who decided instead to stick it out came up with an ingenious way to sell their grapes and still legally make wine, becoming rich in the process.

U.S. law stipulated that grapes could be grown if and only if those grapes were used for non-alcoholic consumption. If it was determined that someone instead used those grapes to make booze, and the vineyard owner who sold the individual the grapes was aware of this, both the grape grower and the winemaker could find themselves in jail. However, if the grape grower gave clear warning that the grapes were not to be used for the creation of alcohol and those grapes passed through enough hands so that even if the end result was wine, the grape grower did not know the bootlegger’s intentions, the grower was in the clear.

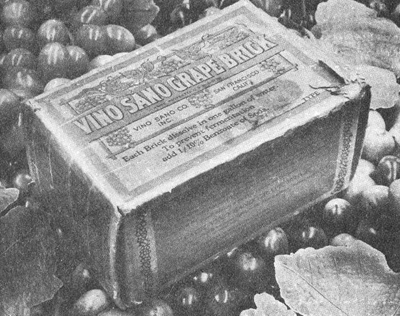

“These were sold during Prohibition era as Bricks to make Grape Punch. The box came with dried grapes with fermentation instructions how NOT to make wine”

The Volstead Act also stipulated that the grape growers themselves could make juice and juice concentrate only if those products were used for non-alcoholic consumption. So the vineyards could still make non-alcoholic wine and that wine could theoretically be turned into alcohol by consumers as long as the winemakers gave clear warning that this was illegal, and they had no knowledge of the end consumers’ intentions. With these loopholes in place, the creation of “wine bricks” and, in turn, the ability for U.S. citizens to continue consuming wine came to be.

A wine brick was a brick of concentrated grape juice – which was completely legal to produce – that consumers could dissolve in water and ferment in order make their own vino. But not every consumer knew how to make wine, so how did consumers know what to do? The instructions were printed directly on the packaging, but these instructions were masked as a warning of what not to do with the product. An ingenious way to get around the law.

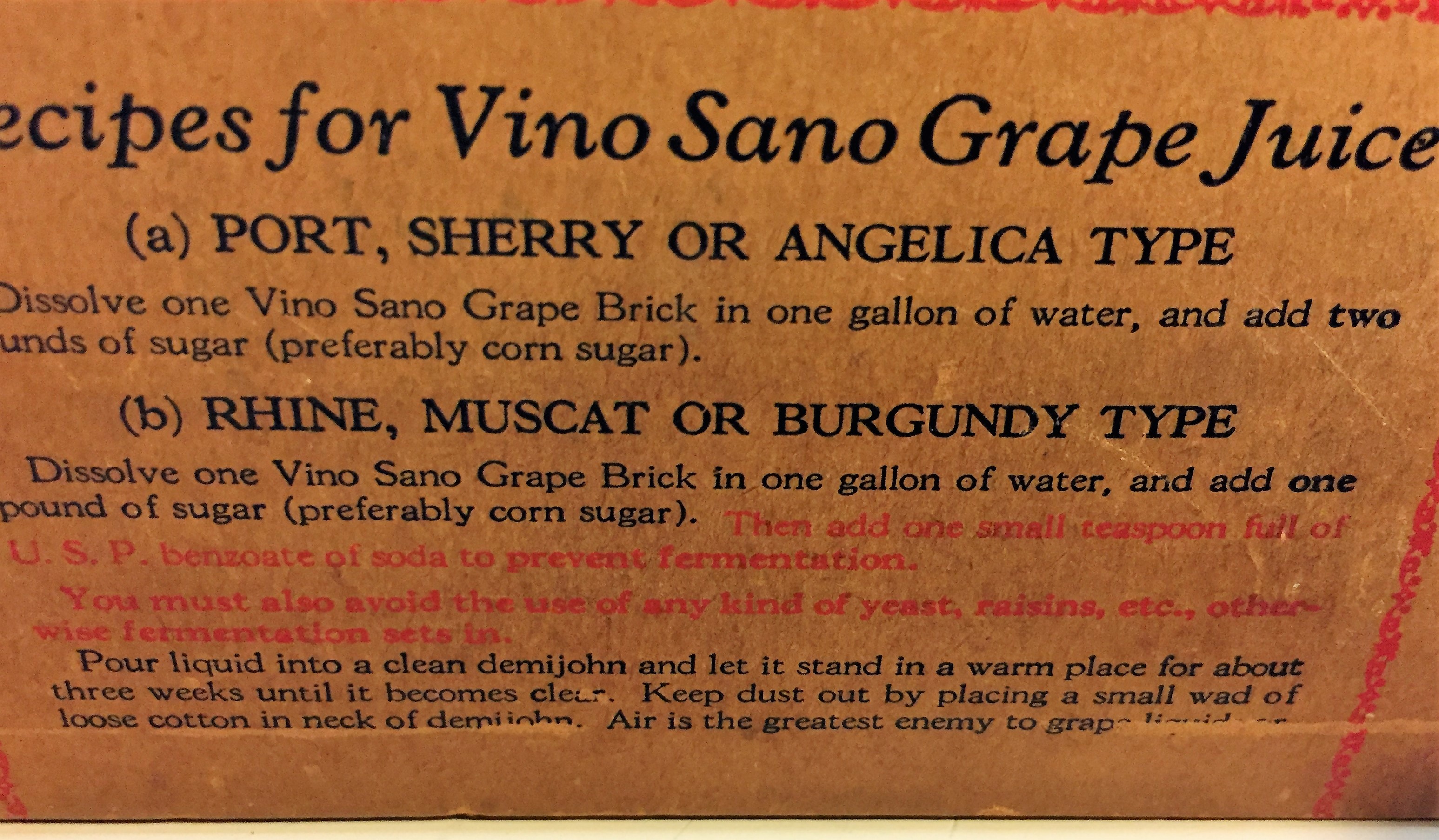

If you were to purchase one of these bricks, on the package would be a note explaining how to dissolve the concentrate in a gallon of water. Then right below it, the note would continue with a warning instructing you not to leave that jug in the cool cupboard for 21 days, or it would turn into wine. That warning was in fact your key to vino, and thanks to loopholes in Prohibition legislation, consuming 200 gallons of this homemade wine for your personal use was completely legal, it just couldn’t leave your home – something wine brick packages were also very careful to remind consumers. Besides the “warning,” wine brick makers such as Vino Sano were very open about what they knew their product was to be used for, even including the flavors – such as Burgundy, Claret and Riesling – one might encounter if they mistakenly left the juice to ferment.

The result of these wine brick was that many people, including the famous Beringer Vineyards, became incredibly rich. This is because the demand for grapes and these concentrate products didn’t fall when Prohibition hit, it rose, but there were fewer people to keep up with the supply, since several winemakers had already torn up their vineyards to plant orchards. By 1924, the price per ton was a shocking $375, a 3,847% increase in price from the pre-Prohibition price tag of only $9.50.

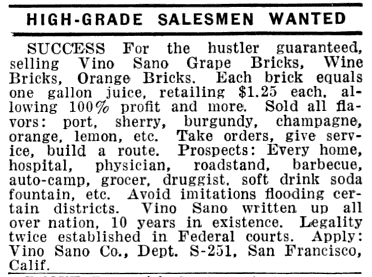

“An ad in Popular Mechanics from 1932 seeking out “hustlers” to help sell Vino Sano grape bricks.”

As prices rose, people from across the country rushed to Napa to get into the grape game. One such person was Cesare Mondavi, a grocer from Minnesota who saw the fortune that could be made and moved his entire family to California to take part. Due in large part to Prohibition, the Mondavi wine dynasty was born. This dynasty and others created thanks to Prohibition insured that California’s wine industry survived and even thrived during America’s dry spell.”

aka ‘GRAPE BRICKS’

https://michelegargiulo.com/blog/grape-bricks-prohibition-wine

https://tastingtable.com/1943655/prohibition-era-grape-juice-warnings/

Prohibition-Era Grape Juice Came With Instructions For Breaking The Law

by Neala Broderick / Aug. 24, 2025

“Throughout America’s notorious veto on alcohol, it was all about loopholes. Between speakeasies hidden behind unassuming storefronts (though there are still unique haunts worldwide today) and bathtub gin, creativity was at an all-time high. Many distilled their own lethal concoctions from home, while others sought approval from religious institutions for sacramental wine or pleaded for a whiskey prescription from their doctor. Just a few years into Prohibition, America discovered a legal way to flirt with the taboos, and everyone seemed to be in on it. The “grape brick” was a seemingly modest, concentrated grape juice block designed to make homemade juice, but it was also the secret to makeshift wine.

The temperance movement didn’t just ban alcohol sales. Prohibition hurt the U.S. by making everything surrounding alcohol illegal, including making it, drinking it, gifting it, and even supplying possible ingredients. Shady business practices were a dime a dozen, but a particularly ingenious one came from vineyards that were suddenly out of work. While they couldn’t legally produce wine, they could sell non-alcoholic wine (grape juice) and leave the last wine-making steps up to the consumer. It came with specific instructions on how to avoid making wine, but in doing so, they subtly provided all of the steps to fermenting a nice red. The coy packaging was littered with warnings, essentially informing consumers that this brick was practically wine, so if you weren’t careful, you might “accidentally” end up with a bottle.

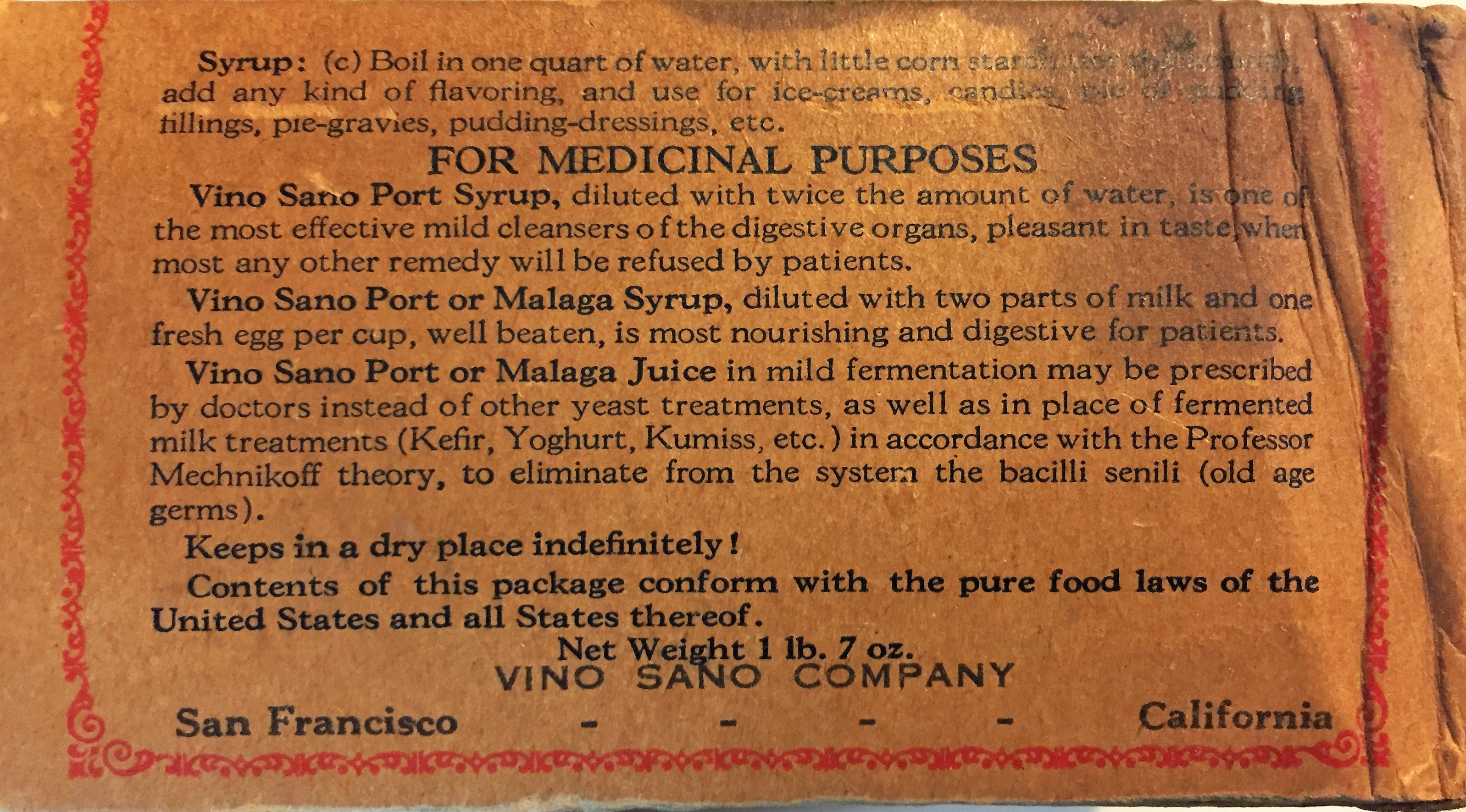

Vino Sano was one of the first grape brick labels on the market, produced by a San Francisco-based vineyard. Some just went ahead and called them “wine bricks,” as the intent was universally understood. But the Vino Sano brick instructions were framed as negatives, including directives such as: don’t dissolve the brick in a gallon of water, don’t add sugar, don’t shake daily, and definitely don’t decant the juice after three weeks. If followed, these steps conveniently produced a 13% alcohol by volume wine. Another tell was the blatant wine-centric flavors. The $2 bricks shamelessly came in sherry, Champagne, port, claret, or muscatel, as Time reported in 1931.

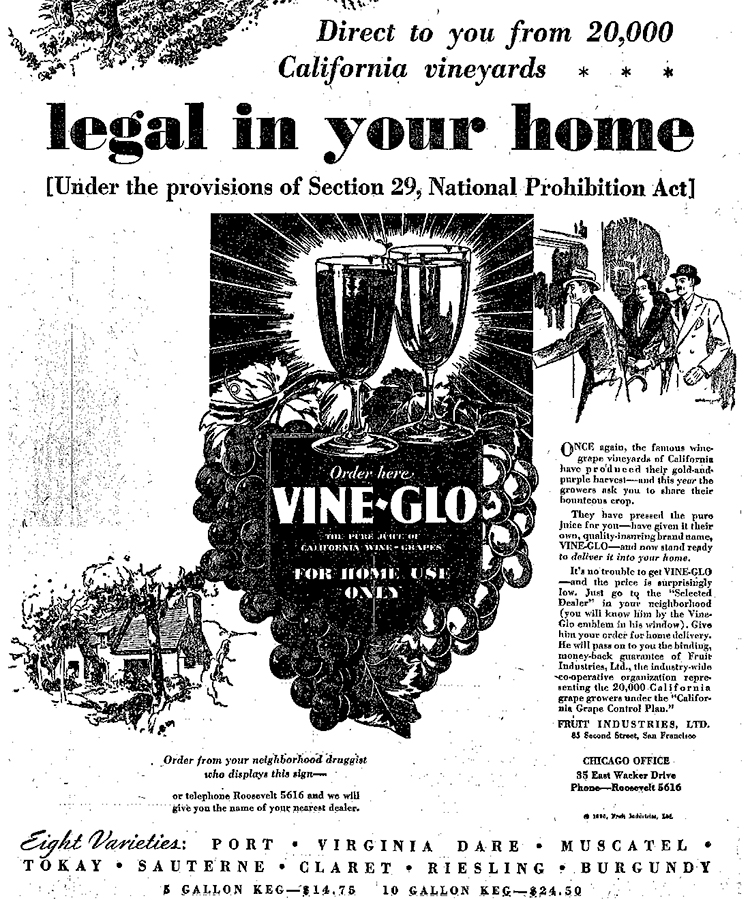

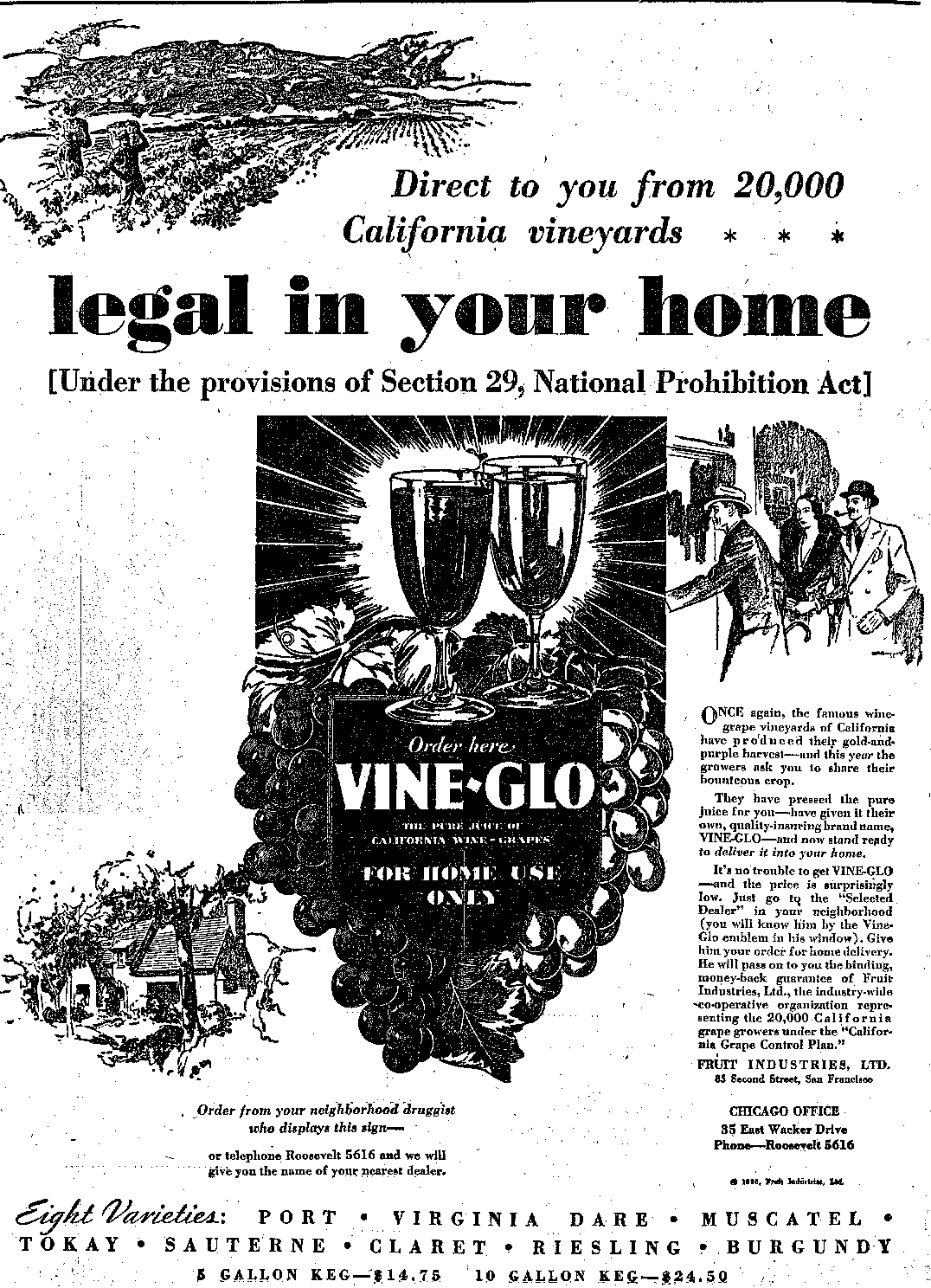

Vino Sano seemed to kick off the innovative scheme, but many other producers dabbled in non-alcoholic beverages that were suspiciously similar to the early steps of wine-making. Vine-Glo was even less subtle, with full wine glasses right on its label. The vineyardists were sure to include the legality of the “juice” as thoroughly as possible, and in the biggest, boldest letters. “For home use only” and “legal in your home” were printed front and center, and even included the specifics of the law they were skirting (Section 29, National Prohibition Act). While there were legal ways to get alcohol during Prohibition, this one was an inventive, hands-on option.”

VINE-GLO

https://dailybulletin.com/rare-brick-that-turned-into-wine

https://theguardian.com/great-dynasties-american-gallo-wine

The Gallos: An American wine-making family in ferment

by Ian Sansom / 27 Aug 2010

“Dr. Johnson in his Dictionary defines wine as “The fermented juice of the grape” – and so it is. And an oenologist, of course, is one who studies wine. And a vintner is a wine merchant. Oenology is not renowned as a family profession, and these days supermarkets are our vintners. But actual wine-making – the process of growing and cultivating grapes, and then the harvesting and crushing and pressing and fermenting and storing and finally bottling and selling of the wine – remains a family business. Family hands vineyard on to family. There are great wine-making families in France, Germany, Austria, Argentina – everywhere fine wines are made. And so too in America, where the famous Gallo winery of Modesto, California is, according to Jancis Robinson in the Oxford Companion to Wine, “the largest single wine-making establishment in the world”. It is also one of the most singular wine-making establishments in the world. The story of the Gallos is the story of a family in ferment.

The Gallo winery was established after the repeal of prohibition in 1933 by two brothers, Ernest and Julio. According to family legend, they read a pamphlet in their local library that gave them enough information to get started. In fact, they’d been unofficially in business for years with their father, Joseph. Joseph Gallo was an immigrant from Piedmont in Italy who established an illegal winemaking and distribution network during prohibition. Joseph was unscrupulous, but he was also a wine pioneer.

“to prevent fermentation, add 1/10 percent benzoate of soda”

One of his bestsellers was something called “vine-glo”, a jellied wine juice that could be turned into wine proper when mixed with water. Joseph made his fortune, but on the eve of the repeal of prohibition, as Ellen Hawkes tells it in her sensationalist biography of the family, Blood & Wine: The Unauthorized Story of the Gallo Wine Empire (1993), he and his wife, Susie, were found dead at their farm in Fresno, California. The official verdict was that it was a murder/suicide – Joseph had shot his wife, and then turned the gun on himself. Others said it was a mob hit. Maybe so: Joseph’s brother Mike is described by another biographer as “the Al Capone of the West Coast”.

Undettered by family tragedy, the Gallo brothers got on with the serious business of business. Julio was in charge of production. Ernest took charge of everything else. As it turned out, according to Jerome Tuccille in Gallo Be Thy Name: The Inside Story of How One Family Rose to Dominate the US Wine Market (2009), Ernest was a marketing genius. He wanted America to be “wine conscious”, and he set out to make Gallo wines “the Campbell Soup of the wine industry”. Julio just wanted to make good wines. Ernest got his way. By the late 1960s they were the largest wine producers in the US…”

LOOPHOLES & WORKAROUNDS

https://historyassociates.com/near-beer-and-wine-bricks

Near Beer & Wine Bricks: Loopholes & Innovation During Prohibition

byJen Giambrone, Historian of such things

“One hundred years ago, the United States was months into a “noble experiment”—Prohibition. Officially in effect as of January 17, 1920, the nationwide prohibition on the manufacture, sale, and transportation of “intoxicating liquors” conjures up images of back-alley speakeasies, flappers and mobsters, and bathtubs full of gin. Opportunists seized the moment, often with tremendous success. But for every gangster and bootlegger, there was a distiller or winemaker faced with economic ruin. We know the alluring stories of crime and corruption, but many others found clever ways to operate within the confines of the law. These lesser-known methods are not as notorious—nor as bloody—but captivate us nonetheless. Here’s a law-abiding citizen’s guide to making a buck during Prohibition.

“A cartoon depicting torpedo juice being produced from the

Dec. 7, 1965 edition of the Omaha World Herald. (David Reamer)”

Find the Loopholes

The 18th Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibited the manufacture, sale, and transportation of alcohol; the Volstead Act, passed in October 1919, enforced it. But the Volstead Act made exceptions for alcohol used for religious or medicinal purposes, and Americans took note. Prohibition threw the California wine industry, which had begun to flourish at the turn of the century, for a loop. At first, demand for grapes skyrocketed, as home winemaking became a popular alternative to store-bought wine. Over time, however, supply outpaced demand and the price of grapes plummeted. Many wineries closed their doors permanently. In the Los Angeles area alone, only about half a dozen of the 90 wineries in the region survived.

“New York City Deputy Police Commissioner John A. Leach, right, watching agents pour liquor into sewer following a raid during the height of Prohibition. (Photo via Library of Congress)”

The winemakers who did outlast the 13-year dry spell often did so by producing sacramental wine for churches and synagogues. This was true of Beaulieu Vineyards in Napa Valley, which rebranded itself as “The House of Altar Wines.” Beaulieu’s proprietors obtained government permits to produce wine and shipped their lucrative libations in barrels marked “FLOUR” to protect it in transit. According to the vineyard’s website, sales to the Catholic Church increased Beaulieu’s business fourfold.

“Because wine plays an important role in Jewish and Catholic rituals, lawmakers made an exception in the Volstead Act for the production and sale of sacramental wine. This loophole was quickly exploited.”

Meanwhile, because priests and rabbis could legally possess and serve sacramental wine during Prohibition, congregations grew overnight—as did the number of people claiming to be priests and rabbis. In the San Francisco area, this type of fraud became so prevalent that the Conference of Jewish Organizations spoke out against it, vowing to “suppress the activity of fake congregations and pseudo rabbis.”

“Although the American Medical Association declared that alcohol had no proven therapeutic value in 1917, the longstanding belief in its medicinal qualities persisted throughout Prohibition, as evidenced by government-issued prescription forms like this one. Source: Wikimedia

Medical exemptions also gave eager tipplers access to booze. Armed with government-issued prescription pads, doctors advised their patients to treat a range of ailments—from asthma and diabetes to cancer and depression—with alcohol. People eagerly paid physicians and pharmacists a few extra dollars for a pint. Historians suspect that the windfall from the sale of medicinal liquor explains how the drugstore chain Walgreens expanded from 20 to 525 stores during the 1920s.

“Although “near-beer” didn’t enjoy as much popularity as its fully alcoholic relative, some companies had success with these products. These advertisements tout the “delicious,” “pure,” and “healthful” qualities of Anheuser-Busch’s “Bevo” and Pabst’s “Pablo.” Source: The Alexandria Gazette via the Library of Congress

Market New Products

Innovation also helped distillers, brewers, and winemakers survive Prohibition. Brewers produced soft drinks, coffee and tea products, malted beverages, infant formula, and even “near beer” with less than 0.5% alcohol. Others stayed afloat by pivoting to other industries—Anheuser Busch and Yuengling, for instance, both began to produce ice cream, as they already had refrigeration equipment on hand. Coors shifted to pottery and ceramics. Enterprising winemakers also introduced a novel product to the marketplace: wine bricks. These blocks of concentrated grape juice came in varieties such as port, claret, riesling, and burgundy—and with warnings that they were intended for non-alcoholic consumption only. Do not dissolve in water and leave in the cupboard to ferment for 21 days, labels insisted, or your innocent grape juice would turn into wine.

“A glimpse inside the wine cellar in Woodrow Wilson’s

private Washington, D.C., home. Source: Library of Congress”

Become President of the United States

Under Prohibition, it was not technically illegal to keep the alcohol you already owned, which was good news for President Woodrow Wilson. While Wilson declined to take a stance on the controversial issue of prohibition during the 1916 election campaign, he firmly supported civil liberties and Congress had to override his veto to pass the Volstead Act. He also had an extensive wine cellar. When it came time for Wilson to leave the White House in 1921, he faced a dilemma: how to transport his wine collection to his nearby home, when to do so would be illegal? Wilson ultimately received special permission from Congress to move his wine with the rest of his possessions—an undeniable perk of being president.”

BONE DRY HUMOR

https://adn.com/atorpedo-juice-the-legendary-illegal-world-war-ii-liquor

https://adn.com/grape-bricks-sneaky-prohibition-treat-in-alaska

Grape bricks: The sneaky Prohibition treat, in Alaska and elsewhere

by David Reamer / April 20, 2025

“For the last several months of 1931, an interesting advertisement ran in the pages of the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner, featuring a detail that would confuse most modern readers. Every week, the generically-named Variety Store on First Avenue declared its existence and specialty: tents, awnings, and hardware. But in late 1931, proprietor Peter Shutz cornered the market on a hot commodity in a decidedly drier time. The Variety Shop was now the licensed Fairbanks agent for Vino Sano’s grape bricks, “natural concentrated grape juice in brick form.” An innocent if curious-sounding product, they were better known as wine bricks, the controversial Prohibition treat enjoyed in Alaska as elsewhere.

The necessary context for grape bricks is the temperance movement, the public crusade to curtail or ban alcohol consumption that peaked in power during the 1910s. Several towns, states, and territories separately and previously banned alcohol consumption, but national Prohibition began with the 18th Amendment, which was passed by Congress in 1917, effective Jan. 17, 1920, and enforced by the Volstead Act. Anchorage was one of the pre-existing dry towns, established in 1915 as a purportedly alcohol-free community. And Alaska banned alcohol with the Bone Dry Act, which took effect in 1918.

It is not hyperbole to declare that Prohibition upended American society. Longstanding, deeply embedded behaviors in an instant became illegal. The culture around alcohol consumption was forced to adapt. As a popular Edward Meeker song predicted, “Every Day Will Be Sunday When the Town Goes Dry.” Manufacturers, retailers, and consumers anywhere along the law-abiding to outlaw spectrum likewise evolved.

There were new products to fill the void and new habits of imbibing, in ways legitimate and decidedly less than. Soda sales and bootlegging boomed. The modern popularity of mixed drinks can also be attributed to Prohibition, as a gagging nation sought options to mask the gut-wrenching taste of low-quality rotguts that flooded the black markets. Some beer companies pivoted to sodas, root beers, ginger ales, and/or legal near beers. Anheuser-Busch, for example, produced non-alcoholic Budweiser and Bevo, a malty soft drink. And unable to make wines, some American grape producers refocused on a burgeoning juice market.

Grape bricks were one innovation among many, a winking attempt to cash in on the gap between demand and supply. Several companies produced grape bricks during Prohibition, but there was little difference in the execution. The name was true to the concept. Grape bricks were nothing more than dehydrated grapes pressed into a brick shape and wrapped in paper. Another nickname was raisin cakes. Dissolve a brick in water and add copious amounts of sugar to produce juice. It’s not a perfect metaphor, but think of Kool-Aid as bath bombs instead of powder packets.< From production to distribution to point of sale, grape bricks contained no alcohol and were thus theoretically legal products. The Volstead Act even included an explicit dispensation for home juice manufacture. Ciders also rose in popularity during Prohibition. But there was a trick, one openly acknowledged by the grape brick companies, even on their packaging.

“A 1920s Vino Sano label.”

Vino Sano was early to market with the grape brick concept, first appearing in 1921. The instructions on their bricks read: “Dissolve one Vino Sano Grape Brick in one gallon of water, and add two pounds of sugar (preferably corn sugar). Then add one small teaspoon full of U.S.P. benzoate of soda to prevent fermentation.” Benzoate of soda is better known today as the preservative sodium benzoate. In other words, if a grape brick preparation was left unattended for a couple of weeks without sodium benzoate, it would ferment into wine. And who would want such accidental bounty while there was a nationwide ban on wine sales?

“An ad for The Variety Store that appeared in the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner on Dec. 4, 1931, references “natural concentrated grape juice in brick form.”

Other grape brick advertising was more obvious. Vino Sano produced grape bricks in various flavors, including port, sherry, muscat, and burgundy. These words just happened also to be the names of wines. An early Vino Sano advertisement called it a “kick in a brick,” adding that the buyer needed only water and “14 days patience.” A 1929 Texas Grape Brick advertisement stated, “For that thirsty feeling get a Grape Brick! In the following flavors: Port, Sherry, Rhine, Malaga, Champagne, Burgundy, Muscatal.” The largest print in Vine-Glo grape brick advertisements was the phrase “legal in your home,” a warning not typically included with completely legal products. Again, at no point were grape brick companies ever subtle.

“This Vine Glo advertisement appeared in the Chicago Tribune on Dec. 8, 1930.”

By all accounts, the result was a foul approximation of properly prepared wine. Yet, grape bricks, or wine bricks as they were often called, were popular. Manufacturers hired attractive women to demonstrate the bricks in stores. They winked, smirked, and smiled while providing warnings against turning the batches into wine, even though it would be ever so easy. The true allure was so evident that many consumers ordered them for delivery from drug stores, not wanting to be seen with grape bricks actually in hand. Vine-Glo was so popular in the Chicago area that its parent company, Fruit Industries Ltd., claimed bootlegging gangster Al Capone threatened to kill their agents for encroaching on his territory. Managing director Donald Conn bravely announced, “Fruit Industries will take its chances with the racketeers,” though he had perhaps invented the entire exchange for publicity.

Grape bricks indeed made their way north to Alaska, becoming part of the local lore. Everyone had a wine brick joke; they were just too easy. Any discussion of construction bricks meant a litany of late-night host-esque responses. When the Anchorage Daily Times ran an article about a brick factory using their kilns to dry food, it included the line “and it is not wine brick, either.” Some grape brick companies offered “home services,” meaning a representative showed you how to (not) make wine. These house calls were discontinued in 1931, and the Daily Alaska Empire, now the Juneau Empire, suggested, “If the housewife forgets how not to handle their product to keep it from fermenting, she will have to write Mabel for directions. That’s where her training in the Prohibition service will have real value.”

The Canteen is mere backstory to the token. The front text is straightforward and concise. “The Canteen Bar, 12 1/2¢ In Trade, Anchorage, Alaska.” The back offers a view of downtown Anchorage looking west toward a setting sun. The top reads, “Native Copper.” credit David Reamer)”

On Jan. 26, 1932, James Wickersham, Alaska’s non-voting delegate to the House of Representatives, testified on the impact of Prohibition in the territory. Illinois Rep. Claude Parsons asked him, “You do not have the wine bricks and the California wine-glo?” Wickersham replied, “No; our folks do not go in for small drinks. When they want liquor, they want liquor, and they get it in British Columbia and bring it over by boats. But we have a good set of enforcement officers and they are enforcing the liquor laws rigorously, too rigorously, many think.” He was unaware or did not want to admit that wine bricks were openly advertised, even in far-distant Fairbanks. Needless to say, the authorities were also well aware of grape bricks and their slippery relationship with legality. Vino Sano owner Karl Offer was indicted in 1927 but acquitted in a jury trial the following year. Their employees were periodically raided and arrested over the years. Still, grape bricks largely survived their many battles with law enforcement, becoming more a part of the establishment as years passed. United States Assistant Attorney General Mabel Willebrandt was one of Prohibition’s most aggressive enforcers. When she resigned in 1929, Vine-Glo hired her to lead their legal team, a sign of the times.

“This Texas Grape Brick advertisement appeared in the El Paso Evening Post on Sept. 6, 1929.”

A mysterious fire ravaged Vino Sano’s San Francisco wine brick factory on Oct. 28, 1932. The blaze ended their lengthy run and signaled the rapidly approaching doom for the entire wine brick market. The Cullen-Harrison Act took effect on April 7, 1933, legalizing beer and wine with lower alcohol content. The 21st Amendment, which repealed the 18th Amendment, was ratified on Dec. 5, 1933. Given legal alternatives, no one wanted to make awful wine at home. Grape bricks almost instantly disappeared from the public consciousness. The American grape industry itself suffered long-term negative ramifications. Producers prioritized cheaper, faster-growing grapes, which saturated the market. Prices plummeted, and it took decades for the California wine industry to recover.

In that happy April of 1933, businesses across the territory placed rushed orders for cases of beer and wine from Seattle. The first cases reached Ketchikan on April 10. Mayor Jack Davies and Mayor-Elect Pat Gilmore posed for a picture with the first legal beers quaffed in Alaska in more than 15 years. The beer was Hemrich’s Select, from a Seattle brewer. Pint bottles sold for 25 cents, a little over $6 in 2025 money. The cases sold out in an instant.”

PREVIOUSLY

HARD TIMES TOKENS

https://spectrevision.net/2013/03/29/hard-times-tokens/

HIGH as CHRISTMAS TREES

https://spectrevision.net/2022/04/20/growing-wild/

the DRUNK HYPOTHESIS

https://spectrevision.net/2025/07/17/history-of-getting-drunk/