“The researchers found monazite crystals forming in the fern.

(He et al., Environ. Sci. Technol., 2025)”

PHYTOMINING RARE EARTH ELEMENTS

https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.est.5c09617

https://sciencealert.com/rare-earth-element-crystals-found-forming-in-plant

Rare Earth Element Crystals Found Forming in a Plant For The First Time

by David Nield / 23 November 2025

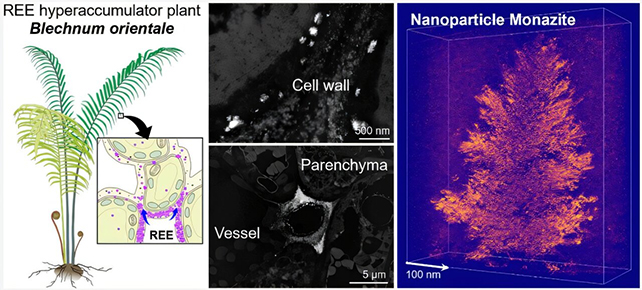

“Scientists have just discovered an incredible superpower hidden away in the tissues of the fern Blechnum orientale, a plant that can collect and store rare earth elements. The findings could lead to a more sustainable way of gathering mineral resources that we are increasingly reliant upon. There are 17 rare earth elements in total, and these metallic materials are now deeply embedded in all kinds of tech – from wind turbines and computers, to broadband cables and medical instruments. They’re not actually that rare, but they are difficult and expensive to extract from the Earth’s crust in a useful form.

That’s where the idea of phytomining comes in, using plants known as hyperaccumulators – capable of growing in richly metallic soils and binding with the metals – to pull mineral resources out of the soil. “Rare earth elements (REEs) are critical metals for clean energy and high-tech applications, yet their supply faces environmental and geopolitical challenges,” Chinese Academy of Sciences geoscientist Liuqing He and colleagues write in their published paper. “Phytomining, a green strategy using hyperaccumulator plants to extract metals from soil, offers potential for sustainable REE supply but remains underexplored.”

“The Blechnum orientale fern”

The B. orientale fern was already a known hyperaccumulator, but the scientists discovered something even more special: it was actually growing REE crystals in its tissues. Via powerful microscopic imaging and chemical analysis, the researchers found the REE-rich compound monazite accumulating as a “chemical garden” inside the plant’s own tissues, self-organizing from elements including neodymium, lanthanum, and cerium. It’s the first time researchers have seen a plant do this.

Scientists are only just beginning to explore the potential of phytomining, but this study suggests that it may have even more potential than originally thought. At least one plant is forming REE minerals under normal conditions, without the high heat and pressure normally needed under the ground. “This discovery reveals an alternative pathway for monazite mineralization under remarkably mild conditions and highlights the unique role of plants in initiating such processes,” write the researchers.

Further research should help to establish whether this is unique to B. orientale, or whether we can expect to see it in other plants too. There are some signs of it happening in another fern, Dicranopteris linearis, but no direct evidence yet. Scientists now hope to develop a way of extracting the monazite and breaking it down into its component REEs without losing too much of the resource along the way. There are challenges ahead for sure, but this could transform REE collection – and the many green energy technologies that rely on it. “This discovery not only sheds light on REE enrichment and sequestration during chemical and biological weathering but also opens new possibilities for the direct recovery of functional REE materials,” write the researchers. “This work substantiates the feasibility of phytomining and introduces an innovative, plant-based approach for sustainable REE resource development.”

“Monazite crystal (not from the plant)”

NATIONAL SECURITY CRYSTALS

https://popularmechanics.com/fern-rare-earth-metals

https://zmescience.com/fern-making-rare-earth-crystals

A Chinese fern builds valuable rare earth minerals atom by atom

by Mihai Andrei / November 14, 2025

“A common fern in China (Blechnum orientale) is performing an act of geological alchemy. It is quietly building microscopic crystals of monazite, a valuable mineral packed with the rare earth elements essential for smartphones, electric cars, and wind turbines. This discovery, researchers say, is the first time a living plant has been found to forge a rare earth mineral. It could open a new, tantalizing path toward a “green circular model” for sourcing the metals that power our modern world. Rare Earth Elements (REEs) are a group of 17 metallic elements with similar chemical properties. Despite their name, they are not all that rare in the Earth’s crust. The problem is that they are usually in very low concentrations. They’re seldom found in concentrations high enough to make extraction easy or economical.

These minerals are critical for many high-tech and clean energy applications as they possess unique magnetic, luminescent, and catalytic properties. This makes them indispensable for the powerful magnets in wind turbines and electric car batteries, the vibrant displays in smartphones, and advanced medical scanners and defense systems. But extracting them from the Earth is often expensive and environmentally devastating, relying on harsh chemicals that can pollute land and water. This is why the new plant can make such a big difference.

This fern was already known to be a hyperaccumulator, able to thrive in REE-rich soils in southern China by absorbing the metals. The researchers from the Guangzhou Institute of Geochemistry wanted to see how it was doing it. They teamed up with an earth scientist in the geosciences department at Virginia Tech in the United States for the work. Using high-powered imaging, the team found the answer. The fern was not just storing scattered metal atoms. It was actively building nanoscale crystals of monazite, a phosphate mineral rich in REEs like cerium, lanthanum, and neodymium.

This is one of the main minerals sought in conventional geological ore deposits. The process appears to be a defense mechanism. The fern is protecting its living cells from these toxic metals by first putting them in “extracellular tissues” — the spaces and walls between cells. There, it locks them away in a stable, crystallized form. It’s like it does all the mining for us. “To our knowledge, this is the earliest reported occurrence of rare earth elements crystallising into a mineral phase within a hyperaccumulator,” the researchers write in the study.

What was even more surprising is how the plant does all this at room temperature. Geologically, monazite “typically formed under high pressure and temperature hundreds of degrees Celsius,” the scientists said. This fern, however, was building the same mineral at ambient, room-temperature conditions. The crystals the plant makes are also of excellent quality. They have a high melting point, excellent optical emissivity, and exceptional resistance to corrosion from molten glass and radiation damage. This discovery, the researchers stated in their abstract, “opens new possibilities for the direct recovery of functional rare earth element materials.”

For now, this is little more than a biological curiosity. But it could become very useful, very fast, if it can be scaled. Of course, that’s a big if. Blechnum, known as hard fern, is a relatively large genus of fern. Blechnum orientale itself is a remarkably well-studied plant, for different reasons. It seems to have antibacterial and antioxidant properties, and can even be used for wound healing. To use it as a serious alternative to conventional extraction, you’d need to plant it in large numbers. There’s also the problem of time. A plant needs time to grow and absorb minerals. Then, you need to extract the materials from the plant and do something (hopefully, something useful) with the plant biomass.

But researchers could potentially also give the plant a boost. If the natural fern is a remarkable proof-of-concept, scientists can now aim to build a “super-miner” plant. Using gene-editing tools like CRISPR, researchers could, in theory, create a plant that is hyper-efficient at the job. Or perhaps, they could find a way to replicate the plant’s mechanism and recreate it in other organisms, like bacteria. The ultimate vision, according to the Guangzhou Institute of Geochemistry, is a self-sustaining loop. “By planting hyperaccumulator plants, high-value rare earths can be recovered from the plants while remediating polluted soil and restoring the ecology of rare earth tailings,” the institute said in a statement. This, it concluded, could realize “a green circular model of ‘remediation and recycling at the same time’.”

“Odontarrhena chalcidica blooms in Metalplant’s fields in

Albania’s Tropojë region in the spring.” Credit: Sahit Muja

BRASSICA MINING

https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acscentsci.5c00049

https://cen.acs.org/Metalplant-farms-nickel-instead-mining

Metalplant farms nickel instead of mining it

by Diana Kruzman / April 10, 2025

“When Sahit Muja was a child growing up in the Tropojë region of northern Albania, Lulja e Qenit was no more than a weed. The bushy green plant with tiny yellow blossoms grew along the side of the road and invaded farm fields and pastures; animals refused to eat it, and locals often tried to burn it. In 2021, Muja, a businessman and developer, got a call from US climate tech entrepreneur Eric Matzner. Years earlier, one of Matzner’s start-ups had been interested in sourcing a carbon-trapping mineral called olivine from a quarry Muja owned in Tropojë.

That start-up ended up sourcing olivine from a different location, and their partnership never blossomed, but Matzner now thought Muja could help him with a different problem: the olivine the start-up was using to capture carbon along coastlines was releasing nickel into the ocean, and scientists feared that could affect corals offshore. But, as Matzner excitedly told Muja over the phone, Albania’s Lulja e Qenit could be the solution. The plant, also known by the species name Odontarrhena chalcidica, is a nickel hyperaccumulator, meaning that it can draw up the metal from the soil and deposit it in its leaves and stems at high concentrations.

Eventually, the two realized that using plants to collect nickel could be a business of its own. That same year, Muja and Matzner, along with operations executive Laura Wasserson, founded Metalplant, a start-up that specializes in a technique called phytomining—a method of extracting metals from the soil using plants—which they apply to farming fields of O. chalcidica and harvesting the valuable nickel contained within it. Albania’s nickel-rich soil makes it almost useless for growing food crops, but Muja and Matzner believe it is perfect for phytomining.

Traditional metal mining “goes against the thermodynamic gradient,” Matzner says. It uses chemicals and heat to extract metals from ores that naturally want to hold on to them. Phytomining, on the other hand, allows plants to do most of the work of extraction, reducing the energy input required. Entrepreneurs are quickly commercializing this technique as demand for nickel grows for applications like electric vehicle batteries. In August, the US Advanced Research Projects Agency – Energy, or ARPA-E, granted $9.9 million to seven projects aimed at improving and scaling up phytomining on US soil. Metalplant was among them, with a proposal to increase O. chalcidica‘s yield and to genetically modify the plant to avoid the possibility of its becoming invasive once it takes root in the US.

“Eric Matzner harvesting Odontarrhena chalcidica in

Tropojë, Albania, in 2024. Credit: Diana Kruzman”

The company is growing at a time when the US seeks to boost the domestic supply chain for nickel and nickel and reduce imports while satisfying demand for the clean energy transition. The company appeals to a niche market, offering less carbon-intensive nickel for more conscious consumers. If it can build that market and scale up, the Metalplant team could lay the blueprint for the expansion of cleaner, more environmentally friendly nickel. More than 700 nickel hyperaccumulators are known to science, but Metalplant chose O. chalcidica because it’s one of the best.

The plant’s biomass can contain up to 2% nickel by dry weight, and its high yield and quick growth can deliver between 200 and 400 kg of nickel per hectare in one growing season, according to Metalplant’s estimate. The US Department of Agriculture’s Agricultural Research Service first developed the field of phytomining in the 1980s, but the effort was a victim of its own success. The agency halted an early project after Alyssum, a relative of Odontarrhena also sourced from Albania, flourished to the point of becoming an invasive species around an Oregon test site.

“Sahit Muja (left) and Eric Matzner in Metalplant’s olivine quarry,

about 40 min away from its fields. Credit: Diana Kruzman”

Now, Metalplant is reviving this technique, hoping to take advantage of the increasing demand for nickel as a critical element in electric vehicle batteries. That sets it apart from other phytomining ventures, such as the France-based start-up Econick, which mainly targets steelmakers. Metalplant plans to market its nickel as an alternative to that supplied by Indonesia, the biggest producer of the metal, whose mining operations are plagued by environmental and human rights abuses. But before nickel can be sold, it needs to be extracted from the plant material. Phytomining companies, including Metalplant, generally start by burning the plant biomass to create a fine ash.

Metalplant then washes the ash, precipitates what’s left, and filters out elements such as potassium, calcium, and magnesium. The product is eventually recrystallized as nickel sulfate. Regardless of the method used, the resulting product comes in a form that steel or battery makers can use immediately, such as a nickel salt or a high-purity nickel ingot, both of which Metalplant offers to buyers. Burning the biomass releases greenhouse gases and somewhat tempers the climate benefits of the resulting metal. Metalplant counteracts this drawback with a carbon capture technique called enhanced rock weathering—the very process Matzner used in his previous start-up.

“Metalplant collects Odontarrhena chalcidica seeds from its fields

and stores them for future crops. Credit: Diana Kruzman”

In the natural rock weathering process, rocks like olivine are weathered by rain and release minerals like calcium and magnesium. These minerals react with the carbon dioxide the rainwater has picked up from the air and produce compounds such as calcium carbonate. This alkaline substance is swept away by rivers and deposited in the ocean, where it is sequestered for up to 10,000 years. To pull off enhanced rock weathering, Metalplant grinds up olivine sourced from a quarry about 40 min from its fields and spreads it on the soil where the nickel-loving plants grow.

The olivine powder weathers naturally and releases nickel back into the soil, replenishing the soil supply for plants to take up through hyperaccumulation. Overall, for every kilogram of nickel Metalplant produces, it removes 200 kg of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere—creating a product the company calls NegativeNickel. But challenges stand in the way of large-scale applications. For the time being, the cost of phytomining nickel far outweighs traditional mining due to its smaller production capacity. Rather than competing directly with major producers in Indonesia, Matzner says that Metalplant is focused on getting commitments from companies such as electric vehicle battery makers or green steel manufacturers that are willing to pay a “green premium” for carbon-negative nickel.

At the same time, he hopes future efforts to combat climate change, such as putting a price on carbon, could make conventionally mined nickel not worth the cost. “My hope would be that if they had to pay for the carbon footprint of their nickel, if they had to pay the cost of the deforestation of their nickel, their nickel would not be competitive,” Matzner says. Colleen Doherty, a plant biochemist at North Carolina State University whose lab is using plants to mine rare earth elements, believes commercializing phytomining will involve more than just finding willing buyers or perfecting the science. “There’s this perception of plant mining as hippie dippy—that it’s not gonna work, it’s not realistic,” Doherty says. “And phytomining still has to contend with that.”

Despite these barriers, Muja sees phytomining as an opportunity not only to secure minerals for the energy transition but also to provide opportunities for people living in areas like northern Albania, where the soil makes agriculture difficult and unprofitable. “As an Albanian myself, I try to create value to my land and my people instead of extracting those resources for very little money,” Muja told C&EN on a ride through the Albanian countryside in early September. He showed off Metalplant’s fields—with the harvest over, workers were concentrating on collecting O. chalcidica seeds. With the marriage of nickel-rich soils and nickel-loving plants, Muja says, “the future is really bright here.”

PREVIOUSLY

METAL FARMING

https://spectrevision.net/2020/03/03/metal-farming/

GEOACTIVE MICROBES

https://spectrevision.net/2020/10/01/radical-geomycology/

METALLOPHYTE PLANTS

https://spectrevision.net/2021/08/16/metallophyte-plants/